The big little differences: What is the difference between longbows, recurve bows, and compound bows? Not as much as you might think, says James Park…

Rather than considering longbows, recurve bows and compound bows to be distinctly different types of bow, think of them as a continuum

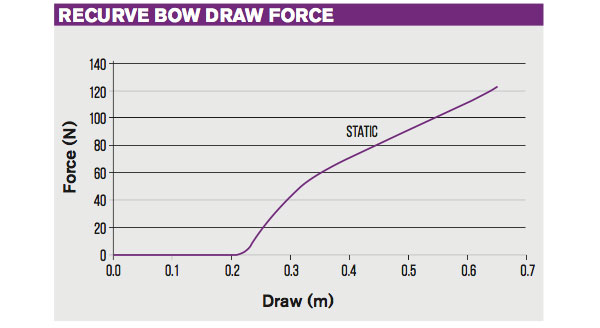

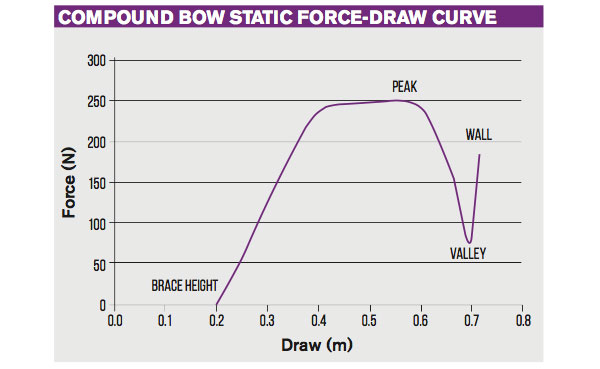

Longbows, recurve bows and compound bows all look different, but what are the actual differences? I know they look different, but if all you could see was the grip and the nocking point, how would you tell which it was? You could perhaps tell from the force-draw curve, but even that could be difficult for a longbow and recurve bow. Interestingly, in the 1930s Hickman showed how you could use an extreme recurve to have the force-draw curve for a recurve bow fall as you neared full draw – rather similar to that for a compound bow.

Rather than considering them to be distinctly different types of bow, I like to think of them as a continuum. Taking quite small steps, one at a time, it is quite easy to move from a straight longbow through to the most complicated compound bow.

Changing the shape of a compound’s wheels allows for the introduction of a valley and wall on the draw-force curve

Starting with a straight-limbed longbow we have a relatively simple force-draw curve, virtually the same as that for a recurve bow. The rate of rise of the force during the first part of the draw is largely dictated by the length of the limbs and the amount of any deflex/reflex and recurve. For a given full draw length, a longer bow will have a flatter force draw curve around full draw. Similarly, it will be flatter if there is more recurve (but that also adds more to the moving mass, which damages the bow’s dynamic behaviour).

We could then add a simple round wheel at the end of each limb with an axle in the centre of the wheel and with the string passing over that wheel and terminating on the axle of the other limb. The shape of the force-draw curve would be approximately the same as for the ‘recurve bow’, although the limbs could now be shorter. Would it now be a ‘compound bow’, even though it would feel like a recurve bow to draw? It would not have a force let-off and valley at full draw – it would still feel like a recurve bow.

The change from a longbow to a recurve can be as simple as a design where the string lies along part of the limb

We could then change the gearing by using two tracks of different diameter on each wheel. However, with round wheels and central axles the shape of the force-draw curve would still be the same.

For the next small step we simply need to start moving the axles away from centre and/or changing the shape of the wheels away from round. Those changes now let us change the shape of the force-draw curve, perhaps now introducing let-off and a valley. Have we got to a compound bow yet? Most people would say we have.

We can then continue to make very small changes in the shapes of the tracks and their number and move through to the most complicated ‘compound bow’ configurations.

The distinctions between a longbow, a recurve bow and a compound bow are, then, rather arbitrary. Perhaps most people would say that we change from a longbow to a recurve bow when the shape of the limbs is such that the string lies along part of their length when the bow is at brace height, and that we change from a recurve bow to a compound bow when we first add a wheel (of any shape and configuration).

Most of the small changes along this continuum of bow design and configuration have occurred as archers have sought to make them more accurate (naturally enough). For example, sights were added to longbows so that archers could aim more accurately, recurves were added to make the bows smoother around full draw and to store more energy, clickers were added to recurve bows to ensure a consistent draw length, wheels were added to recurve bows to modify the force-draw curve, release devices were introduced to enable a more consistent release. I have been an archer long enough to recall using sights on longbows and peep sights and release devices with recurve bows, none of which is now permitted in normal competition.

The equipment rules set quite arbitrary break points along this continuum of bow technology. Mostly those arbitrary points are set in such a way that they limit the ease with which that particular class of bow can be used accurately. For example, there is no inherent reason why a longbow should not have a sight (many used to have them in the past) or a recurve bow have a peep sight. They are simply decisions by our governing bodies aimed at trying to sensibly delineate the different categories.

This similarity between the bow types tells me that we should also see a lot of similarity between the archery techniques used with them. Good technique for a recurve bow is usually good technique for a compound bow or longbow.

This article originally appeared in the issue 116 of Bow International magazine. For more great content like this, subscribe today at our secure online store www.myfavouritemagazines.co.uk