Hugh D. Soar examines arrows from the past, and reveals what they might be able to show us about historical warfare and craftsmanship

Traditional archery is not noted for mystery, but certain items recovered from the ‘Mary Rose’ have had traditionalists – and others with a nose for the unusual – puzzling over, of all things, arrows.

As we all know, or should, arrows traditionally have one of four profiles. These are parallel (straight) bobtailed (tapering from pile to nock), breasted or chested (tapering from nock to pile) and barrelled (tapering to both nock and pile from broadly the shaft centre).

However, among the many shafts recovered from the ship, there is a fifth profile, known to those who are familiar with it as ‘saddled’. That is, a shaft with two distinct ‘barrellings’, separated by a central ‘dip’. Over 30 of these were examined for ‘Weapons of Warre’ – the Mary Rose Society’s archaeological report – and their details, including a sketched profile are contained within Chapter 8 of Part One.

But, although ‘saddled’ shafts no longer survive, we may ask – what was their purpose? Let us speculate. The profile embodies one ‘barrel’ forward of centre, and one aft. It also has a substantial head, as does a ‘bobtailed’ shaft. So, it incorporates two aspects of other profiles. What are these? A bobtailed arrow carries a heavy head to slam through plate, while ‘barrelling’ reduces vibration, particularly immediately following release, thereby (in theory at least) improving distance. Since the ‘saddled’ shaft includes the primary characteristics of both, did some sixteenth-century theorist hope to produce a battle shaft capable of delivering a heavy head with a shaft profile designed to reduce vibration and thus increase its effective distance? Obviously we will never know, and so far to my knowledge no-one has carried out the experimental archaeology necessary to find out.

Whatever the reason, the ‘saddled’ shaft has for too long been in history’s dustbin. The thought that an out-of-the-ordinary sixteenth-century concept may actually have got further than the drawing board may be the vital spark necessary to kick-start some contemporary theorist with a similar bright idea. We shall never know the true purpose of the ‘saddled’ shaft, however, if someone within the English War Bow Society (of which body I am proud to be Patron) cares to carry out practical experiment I for one would be interested to know the results.

A word of caution though. There are two alternative explanations contained within ‘Weapons of Warre’. One suggestion from

distinguished bowyer Chris Boyton, is that water immersion, causing degradation of the shafts, may be the reason for the odd shape, while I myself suggested the possibility of poor workmanship. In retrospect however, there is perhaps too much symmetry between the 32 shafts noted with this profile for either of these alternatives to be likely, and we are therefore left where we began, with a mystery.

There are one or two other curiosities associated with these survivors from our archery past. Of the total of 9,600 arrows shown on the ship’s manifest, 2,303 whole arrow shafts were recovered, and of these a random sample of 1,051 were examined in detail. Poplar predominated, followed by birch. No ash shafts were sampled, suggesting that, despite Roger Ascham extolling its virtue for military arrows in his work ‘Toxophilus’, it was seemingly not always the fletcher’s choice.

A greenish substance remained on the shaftments of a number of arrows, and subsequently speculation arose that copper verdigris had been applied – possibly to counteract possible damage by infestation – at or shortly after the stage of fletching. To check whether verdigris was present, one typical shaft was taken to the Royal Armouries for x-ray fluorescence analysis.

This produced an interesting result, since unexpected traces of zinc were found at all points of the shaft up to 100mm from the cone. Copper traces were also found along the shaft, in particular an amount at the shaftment, and a lesser, but still appreciable quantity, at the cone. The presence at the shaftment is understandable, but copper at the head was unexpected. So, why was it there? The coating of arrowheads with copper is not unknown; examples have been excavated. Now, copper is poisonous when introduced into the bloodstream, and wounding with an arrow bearing copper traces at its head would certainly hasten death. There is some evidence that the French accused the English of using poisoned arrows. Could this be proof?

While technically the war-bow remained part of this country’s armoury until well into the seventeenth century, and indeed featured in occasional skirmishes during the Civil War, its steady replacement by the hand gun lessened the need for practice. Although the old Statute requiring adult males to shoot at no less than 220 yards was no longer generally observed, this was recognised as a target distance by those recreational archers who shot on London’s Finsbury Fields, some of whom had, in the early seventeenth century, formally created the Society of Finsbury Archers, the earliest English recreational archery club. ‘The ‘Eleven Score Target’ was an annual event for this Society from 1672 until 1752. Oddly, archery practice remained Statute Law until the mid nineteenth century.

The transition from military archery to shooting for pleasure brings another mystery, for although, as might be expected, bow draw-weights dropped, arrow lengths shortened. It is not clear exactly when this happened, since no datable seventeenth century arrows survive, but by the mid-eighteenth century arrow shafts were just 27 inches long; pale imitations of the 31 inch battle shaft shot by lusty English bowmen.

We know something of the making of the seventeenth century recreational arrow from an account preserved in an early book. The final phases in the preparation of the shaft are said to have been: ‘Poising the arrows is to know whether the pair of arrows be of an equal weight as they are of a length. Turning them is to give them a twist in one’s hand to know whether they be straight’. Although the pair were evidently compared with each other and presumably corrected if there was a difference, we can only guess whether, at such an early date, the weight in coinage was marked on the shaft. Paired arrows were shot individually as late as the early nineteenth century.

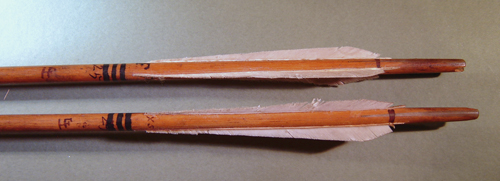

A pair of arrows in my collection, Scottish and datable to the 1760’s, have straight 27 inch self-shafts, four inch triangular fletchings and – curiously – turned brass piles, the earliest examples of this form known to me. The markings tell something of them. An X gives the weight (10 shillings measured against silver coinage) 27 indicates the length and 25 (yards) the distance appropriate to the arrow. These belonged to a member of the Royal Company of Archers who shot at a short distance indoor butt. Comparison shows remarkable similarity. Each weighs 725 grains, and has a spine deflection of .250 thou.

While marking weight by coinage was a regular feature of arrow-making by the turn of the eighteenth century, there was another means of identification used by a member of the ‘Woodmen of Arden’ – a prestigious late eighteenth century archery society. This Society regularly shot ‘the roods’, an early expression for shooting at butts. A rood was an archaic measure of 7½ yards.

Late eighteenth century or early nineteenth century arrows in my keeping are marked either 12 or 16 (roods) indicating their suitability

for 90 yards or 120 yards. These 27 inch long straight self-shafts also appear to have been ‘paired’, and it has been interesting to compare four, each marked 12, for weight and spine, and also head, since there is a deal of difference between these early heads. Heads were made individually by wrapping a piece of sheet metal around a stopping and then brazing the join, a process which carried on until well into the twentieth century and the coming of brass and metal turned piles.

Comparison between two of these shafts showed deflection values of .625, and.650 thou: and an exact weight match of 310 grains. Two others however each weighed 380 grains, although the shafts showed deflections of .525 and .300 thou: With ‘spine values’ yet to be scientifically determined, they may well have been supplied as a ‘matched’ pair.

Finally, a word about fletchings. Those familiar with early arrows will know of the long triangular shape so closely associated with them. What may not be widely known, however, is the reason for the late nineteenth century change to the shield shape largely in use today. It seems that one day in the late 1870’s, Henry Elliott, a member of Aston Park Archers, and a gun-smith by profession, accidentally broke the first three inches from one of his fletches. Some archers might have removed and replaced the affected feather, but not Mr. Elliott. Removing a similar amount from the other two and refining the shape to a shield, he shot the arrow and noticed that it flew better and further. The principal arrow-makers were not slow to pick up this change and the result – as they say – is history.

Of the six 18th century arrows that you have posted all the fletchings seemed to be glued on without any thread wrapping. Was that common in the 18th century?

On the Scottish feathers they were clipped was this common or was it something that only the Scotts did?

The six arrows show what we would call cresting today. Would this had been for identifying the specific archer?

Lastly, do you have any photos of the wrapped steel points or could you tell me were I could view some photos?

Archery has always been a passion for me. I own three English Longbows among others.There are some events held near me that I would like to dress in period and demonstrate late 18th century and early 19th century English Archery.

I am interested in any photos of original dress and equipment for that period. Any help or advice would be greatly appreciated.

Thanking You in Advance,

Tom Talley