By Kristina Dolgilevica

The Way of Archery was first published on February 28, 2015, by two Chinese history enthusiasts-researchers, Jie Tian and Justin Ma. These two American-based authors shared a common goal – to promote Chinese culture to a wider audience in the English language, using archery as a tool. Many have translated and annotated the scrupulously detailed 17th century treatise written by Gao Ying, the Ming Dynasty author who wrote his Chinese military training manual in 1637, and it is a source commonly used by archers today. Active practitioners of archery Tian and Ma not only make this text accessible and remarkably practical, but they also present their interpretation of the philosophical and spiritual aspects of the Manual, helping us better understand and connect with the ancient Chinese warrior; there is always a purpose to the practice. We sat down for a double interview with the authors to find out a bit more of how and why this book came to be.

How did you two meet?

Justin Ma: Back in 2011, a mutual acquaintance of ours, Zhang Li of Alibow, introduced us. [Alibow: traditional archery equipment manufacturer from Fuyang, Anhui, China, est. 2003.] He happened to know both Jie and me, and that we both lived in the US at the time and both had a great interest in traditional Chinese archery.

How did the idea about the book come to light and why Gao Ying’s manual?

Justin: Our book was more of Jie’s idea, I would say. I was reading and studying Gao Ying independently before I met Jie, but he suggested translating it into English and publishing it. My initial reaction was, “are you sure about that? – that’s quite an undertaking!” However, it was Stephen Selby, who translated parts of Gao Ying’s First and Second books, offering a tantalising glimpse into the Gao Ying canon, which started me off looking more closely at his writings, particularly because what he was saying was quite structured. Selby’s partial English translation can be found in his book Chinese Archery (1st ed. 2000, Hong Kong Press), which I highly recommend to anyone interested in Chinese archery. I would like to take the opportunity to thank our publishing company, Schiffer for doing a great job at helping us present our work. I must add that Jie is responsible for the book’s calligraphic cover design. The calligraphy is special and is one of the earliest examples of the Chinese bronze script, another underrepresented part of the Chinese culture.

Jie, how can we learn about the Chinese culture through archery?

Jie: I see archery as a good tool through which one can really show Chinese culture, because the practice is so important throughout Chinese history. If you talk about Chinese culture, there are three key philosophies: Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism, and archery was an important aspect of the first two. In Confucianism, archery is held in great esteem and is one of the gentlemanly, junzi skills (junzi – a son of a nobleman, an “exemplary person”). Royal members who want to become part of the court have to master the arts, of which top four are the Big Arts, ritual, music, archery and writing; there are others. I have recently learned that in Taoism archery represented the way of the universe, the way of nature. In archery, if you hit too high – aim lower, if you overdraw – draw a bit less, kind of like how the nature works, or like how archery practice works. It reminds people that nature’s ways are about balance. Unfortunately human nature tends to do the opposite, to seek to gain more and more – whereas we should be moderate and share with others with generosity like mother nature. The powerful should protect the weak, the rich should give to the poor.

So this is really how Justin and I decided to write this book – as a way to present Chinese culture to people unfamiliar with it – and Gao Ying’s book is perhaps the most detailed book on Chinese archery available. Most archery forms and cultures share a lot of similarities, – it is not like Chinese archery is fancier; we are all humans, two hands, two legs; it is a lot easier to show people similarities between the cultures before talking of the differences. We wrote this whole thing in good faith; we tried it out, we did our best – we stand by it and present it to others. We also really appreciate everyone who has helped us in the process. We did not produce this book for money, we did it out of passion; both of us also wanted to understand our own culture better.

Can you tell me a bit more about Gao Ying; who was he?

Justin: Gao Ying is an author from the 17th century in the Ming dynasty. His manual was published in 1637 when he was 67, and it was his accumulation of 40 years of archery experience. It’s a very famous manual in Chinese archery circles because it’s exhaustive and it’s detailed on technique. However, there wasn’t an accessible version of it for new archery students to study. As Jie mentioned earlier there are many similarities between different archery cultures, no matter the culture one studies. Jie and I are presenting archery through a Chinese cultural lens, and we both feel it can provide a good insight into the culture as a whole; Gao Ying touches on that notion in his work too.

Gao Ying wrote a lot, and you have to read everything to fully understand it. He is a proper archery fan, a real scholar. Gao Ying is by no means a sage, he has his flaws – he had been through a lot of trials and turmoil to get to where he is. He also comes over as a real person – something of a grumpy old man, which comes through his writing really clearly! The thing that annoys me the most is when people say, “You only need to read one chapter or one section to get what Gao Ying is about”. That means that the person has not read the whole book. There are so many wonderful titbits and anecdotes that complete the picture of what is technique and also what is mindset. I really like Gao Ying, he has a dry sense of humour, and it is fun to appreciate that, but you have to read the whole book to get the full picture.

Who handled the translation?

Jie: Gao Ying was from my region so luckily I can understand his dialect, because he uses that in his writing also. So I handled most of the translation, and to do that you need to translate the classical Chinese to modern Chinese to gain better understanding. Justin would handle most of the English translation, which I would also then double-check. We double-check each other. So it was a lot of work – we had to wake up early, but our passion for the task got us out of bed!

Photographer – Ihsan Halimun

Working with historic documents presents big challenges; what challenges have you encountered?

Justin: It was difficult. It was a long process, having to read through that whole manual, to decipher all the classical Chinese grammar as well as understanding the actual physical movements. I grew up in the United States and I am not 100 per cent fluent in the classical Chinese. I speak with the modern dialect, so I had to study up on classical Chinese grammar, plus there was the added challenge of dealing with the historical dialect. It is almost like learning computer language, where you have to go on a new learning curve to bridge the gap between the languages. The key difficulties would be in literal interpretation, for example [Chinese phrase], literally means “straight as a beam”, but if you took that literally and applied it to technique you would actually end up with hunched shoulders. There would be many moments where we would go back and question “what does this mean?”, double-checking, triple checking each other.

Jie: In general, it was hard, definitely. We tried our best, and I am really glad we did. I see it as our contribution to Chinese culture. People often read one passage and think they know everything, but it’s not that easy. Archery is basically draw and release, but there is also a lot of stuff going on behind it – it is an art form.

What do you think attracts people to Chinese archery?

Jie: Chinese culture is one. Here in the US, I have never come across Chinese archery programmes before, but now we have a HEMA school established here, and it has been 11 years since we started The Chinese Archery Programme. There is a lot going on and it offers easy access to newcomers and to the more experienced to come and experience Chinese culture. I think that besides the cultural similarities, what attracts people is also the differences – it is always interesting to see the different ways others do the same thing.

Can you draw any comparisons between the Korean, the Japanese, the Mongol, or other approaches to archery?

Justin: There are two main aspects in Chinese archery, technique, and the culture, with its history and philosophy. Let me briefly mention one ritual. 射禮 (Simplified Chinese: Shè lǐ), or the archery ritual, was one of the key rituals for selecting rulers back when China was more divided into kingdoms and fiefdoms. Rulers were chosen based on how they did in an archery ritual, and for that reason archery was always held in high regard. In addition to that, rulers were not only developing cultural skills through archery, they were developing military skills too. The bow was very much a part of it and was still held in high regard in later dynasties, like the Sung dynasty, 10th – 12th centuries. In those times you were tested for archery, that’s what the generals did; they did so in Ming dynasty, Gao Ying’s period, and the succeeding Ching dynasty.

Confucius himself was an archery teacher, and there is a lot of Taoist lore that features archery, especially the stories about courage. This folk story of the Taoist philosopher Lie Zi (列子) and the Taoist monk Bohun Maoren (伯昏瞀人) best exemplifies it:

“Bohun Maoren stood near the edge of a cliff to shoot, with his back facing towards the canyon below. Each time he shot, he took a step closer to the cliff until part of his feet were hanging over the edge. He could still hit every time.”

You may be fine practising archery in a controlled setting, but if you are facing down the edge of a cliff, you may freak out and lose focus; then you have not truly mastered archery, because you lack the element of the soul and courage which you must develop.

What of the technical comparison?

Speaking about the basics on the technical level, with respect to Korean, Mongolian, Japanese, the commonalities are in the thumb draw, a bow with a straight and very simple handle, and the arrow being put on the right side for a right-handed archer [in contrast to the Mediterranean style]. In terms of style, there were various styles of Chinese archery. When Gao Ying wrote his book, he was comparing and contrasting different styles of Chinese archery practised at the time with different body alignments; some with hands below the shoulders, some with hands at the shoulders or slightly above the shoulders. Gao Ying’s style, the Inchworm technique, is where the hands and the forearms start a little bit above the shoulders and you are pushing downwards towards full draw, in an alignment where the bow shoulder ends up being a little lower than the bow hand, which is done to avoid injury. Gao Ying had a long career where he dabbled in various techniques and he finally settled on this, because he had been trying other methods that were popular, and some of those resulted in him getting an injury. And so his advice in his archery manual was to practise in a way that didn’t incur injury. And you can see it in Korean archery, the Japanese or Mongolian, and even in English longbow technique. It is also true of Amazonian tribes or some African elephant hunters, they will use that alignment as well. In my video on draw I touched upon the subject of postures of archery in different cultures and almost all of them have a sort of common style. As for the key differences between Chinese archery and other types, the most obvious is the ring itself.

What are the biggest difficulties archers encounter when learning technique? Why?

Justin: Interestingly, you would think that the thumb ring would be the most challenging aspect, but actually people get used to it relatively quickly. One of the most challenging beginner elements is the bow shoulder, the most important element which you must get right from the start. It is not intuitive for people who have practiced Olympic archery for a long time, for example. If you are drawing military bows you have to take another adaptation to prevent injury first and foremost; the bow shoulder must stay down and be retracted, along with the rotation of the elbow – those three points save you from injury. For the more intermediate learners it’s the release. Keeping yourself to a high standard is hard, and you must keep everything in place without creeping forward. But if you are not aware of it, it will throw the shot off. You really have to practise it up to a point where you feel that little bit of hesitation, to realise you weren’t expanding fully through the release. You will have a more forgiving shot if you expand properly. The challenge is developing that feeling, and, most importantly, hold yourself to that standard. Luckily, we are in a wonderful era where you can film yourself and act as your own coach if you know what you are doing.

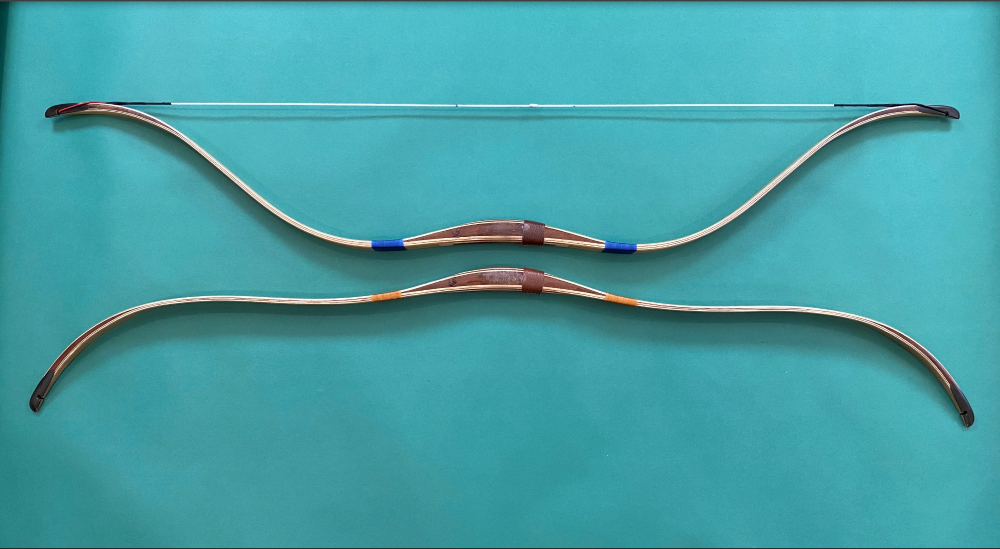

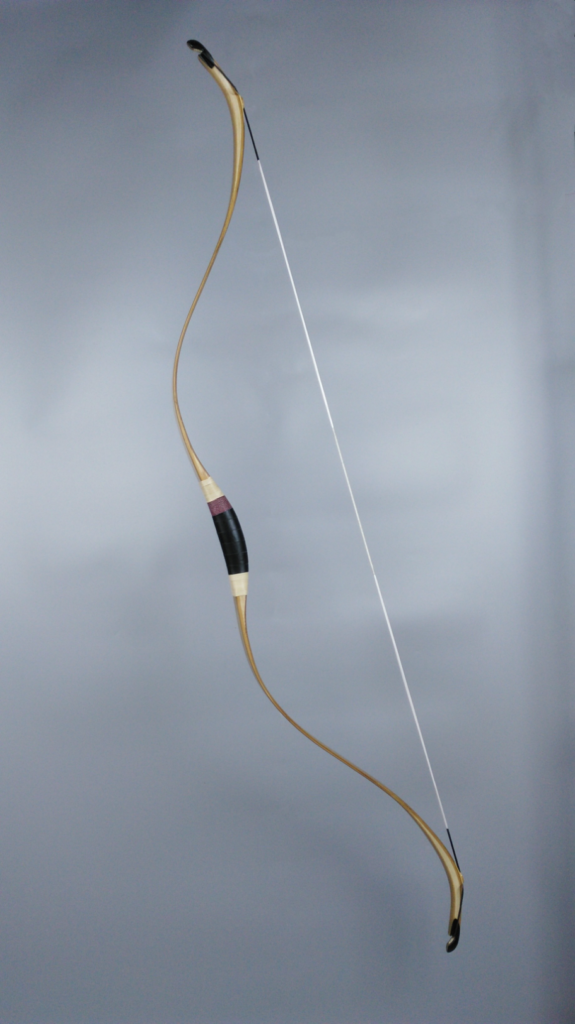

Jie’s favourite bow is Spearman Xiaoshao Bow (小稍弓) designed by Laoqiang (老槍), a bowyer from Jiangsu province. This bow was a mainstay of the Ming archery arsenal. (Shown above)

If you could give one piece of advice to the student of the bow, what would it be?

Justin: Practice even a little bit, make it a part of your life.

Jie: Use “The Way of Archery” as a tool to discover and also appreciate the way of life, the way of the universe.

Thank you, gentlemen and I wish you further success in your work!

Useful Info

For more information on the book, training programmes, and events visit www.thewayofarchery.com; technique tutorials can be found under “tutorials” section.

The Way Of Archery book is available worldwide – check online and offline vendors

Make sure to visit the excellent Youtube channel @TheWayofArchery

Contact the authors: thewayofarchery@gmail.com

Timeline of Chinese Dynasties

Shang (Yin) Dynasty 商 (ca. 1300–1046 BCE)

Zhou Dynasty 周 (ca. 1046–256 BCE)

Western Zhou 西周 (ca. 1046–771 BCE)

Eastern Zhou 東周 (770–256 BCE)

Spring and Autumn Period 春秋 (770–481 BCE)

Warring States Period 戰國 (481–221 BCE)

Qin Dynasty 秦 (221–207 BCE)

Han Dynasty 漢 (206 BCE–220 CE)

Former/Western Han 前漢 / 西漢 (206 BCE–8 CE)

Xin Dynasty 新 (9–23)

Later/Eastern Han 後漢 / 東漢 (25–220 CE)

Wei 魏 Dynasty (220–265) / Three Kingdoms 三國

Jin 晉 Dynasty (265–420)

Western Jin 西晉 (265–316)

Eastern Jin 東晉 (317–420)

Northern and Southern Dynasties 南北朝 (420–589)

Sui Dynasty 隋 (581–618)

Tang Dynasty 唐 (618–907)

Five Dynasties 五代 (907–960)

Song Dynasty 宋 (960–1279)

Northern Song 北宋 (960–1127)

Southern Song 南宋 (1127–1279)

Yuan Dynasty (Mongols) 元 (1271–1368)

Ming Dynasty 明 (1368–1644)

Qing Dynasty (Manchus) 清 (1644–1911)

Reference: Wiebke Denecke, Wai-Yee Li, and Xiaofei Tian (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Classical Chinese Literature, Oxford Handbooks (2017; online edn, Oxford Academic, 5 Apr. 2017