Duncan Busby demystifies the defining feature of a compound bow

Since their introduction in the 1960s compound bows have stood out amongst more traditional recurves or longbows due to one specific feature: their use of a cam system. The cams on a compound allow the archer to comfortably draw and hold a heavier draw weight, they maximise the bow’s energy and efficiently store and deliver it throughout the shot cycle.

Over the years cam technology has developed as manufacturers look for more efficient ways to deliver faster arrow speeds and create more stable, easy-to-tune bows.

Today there are several different cam systems available, each with their own merits and disadvantages. The one you choose will be dependent on what you want from your compound bow.

Twin cam system

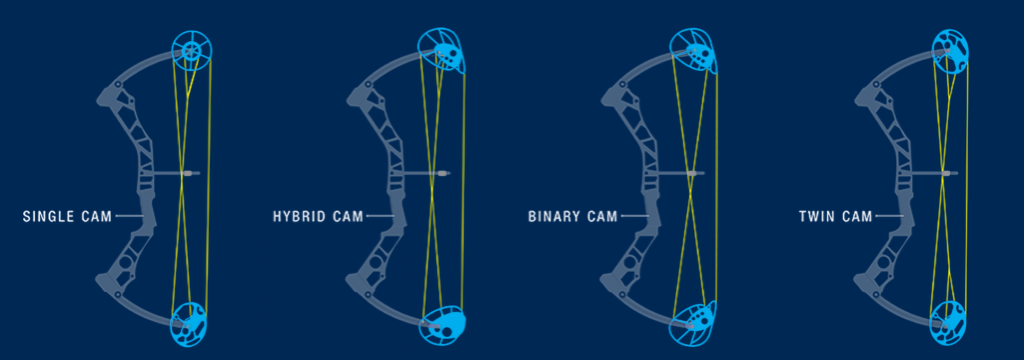

The twin cam system is the oldest design still in use today; it uses identical cams attached to the ends of the limbs via an axle, synchronised using two split-yoke cables and a string. The cables on this system attach to the cams on one end and to the bow’s axle on the other, usually on the outside of the limbs.

Twin cams are praised for their speed and their ability to deliver perfectly straight nock travel. They do, however, require some work in order to get them correctly synchronised and rotating at the same time. Once set they are more prone to coming out of sync, thereby changing the tune of your bow and creating poor arrow flight.

This can make them harder to maintain but with the development of better string materials it is much less of an issue today. The twin cam systems use of two split-yoke cables allows you to easily adjust the lean on both the cams when tuning, therefore simplifying the process as there is no need to change spacers or remove the cam.

As technology has advanced there are now less bows fitted with twin cams although some manufacturers still favour this system due to its simplicity and cost effective application. You can find a twin cam system today on the Hoyt Kobalt, PSE’s Core Series Hunting Bows and Martin’s HTR and Trident models.

Single cam system

The most basic of the cam systems is the single cam. This system uses an asymmetric cam attached to the bottom limb and a round idler wheel on the top. Only the cam on the bottom limb is doing any work, as the wheel at the top merely acts as a runner for the string. The string runs from the cam, over the idler then back down to the cam where it attaches to the opposite side to the string. This system also uses a single split-yoke cable to attach the top limb to the cam.

One of the main benefits to this system is the ease in which it can be set up, as there is only one cam there are no problems with synchronising two to work together. Because of this, single cam bows stay in tune longer and tend to require less maintenance. They’re also smooth and quiet to shoot, producing very little vibration or hand shock.

Although they are easier to set up and tune single cams tend to be slower than other cam systems, which can be an issue for archers who require maximum downrange arrow speed. They can also be problematic when it comes to nock travel, as there is only one cam the lack of symmetry can cause slight variations in the way the string is tracked back into the cam.

This can cause the arrow to be pushed high or low in the bow, though in practice this doesn’t pose a huge problem and tuning a single cam bow is often no harder than with any other cam system. Many records have been achieved with single cam bows proving they can perform in the field, though much like twin cams the single cam system has seen a drop in popularity recently.

Despite this they remain popular with archers due to their low maintenance and simplicity. You can still find single cam systems on the Mathews Conquest 4, PSE Stinger and the Bear RTH range of compound bows.

Hybrid cam system

Made famous by Hoyt with their cam and a half system, the hybrid cam works in a similar way to the single cam but instead of an idler wheel, the top limb has a control cam which is almost identical in shape to the bottom cam. The cams are synchronised using two different cables: a yoke cable and a control cable (and of course a string).

The control cable links the two cams together making sure they work in sync with each other while the yoke or buss cable attaches the bottom cam to the top limbs. The addition of a single-yoke cable makes it easy to adjust cam lean when tuning.

The hybrid cam is designed to give you the practicality and easy tune of a single cam while being as fast as a twin cam. In reality this system is faster in action than the single cam but does require some synchronising beforehand. Once set up though, a hybrid cam bow is very easy to maintain and delivers consistent performance.

Much like a solo cam, hybrid cam bows can suffer from poor nock travel, although this is uncommon and can often be tuned out with a little patience. While they sometimes require a bit more tuning than simpler cam systems, hybrid cams remain a favourite with many archers who value the low maintenance performance they offer. This style of cam is available on the Hoyt Stratos and some Bear RTH models.

Modified twin cam system

The final system is the modified twin cam. Originally designed and made famous by Bowtech this system is still relatively new in archery terms. Sometimes referred to as a binary cam, this system is comprised of two symmetrical cams which are synchronised via two identical cables, which are attached to the cams rather than the limbs so there are no split yokes.

As the cams are synchronised together they cannot work independently, so almost always deliver perfectly level nock travel. Despite this they do require synchronising so that they rotate at the same time but should they come out of sync it will have much less of an effect on your bows performance.

As the modified twin cam system has developed, the cables have been altered in order to give the cams maximum stability throughout the shot. The most common of these variations are the three track and the four track cams; the four track cam is most distinctive as it has what looks like a split yoke. This, however, doesn’t work in quite the same way as a traditional yoke cable as it attaches to the cam rather than the limb, which means it often can’t be used as a way of adjusting cam lean.

Modified twin cams give good arrow speed and are low maintenance but due to their design can suffer with cam lean which can be tricky to tune out. To remedy this manufacturers have developed a number of solutions often using different sized spacers which fit on the axle between the cams and the limbs. Shifting the position of these spacers (often known as shimming) will alter the way the cam leans, allowing you to tune out any left and right arrow flight issues and once tuned, modified twin cams should stay that way for the life of the strings.

Modified twin cams have gained popularity in recent years with the majority of manufacturers now favouring this system on their flagship ranges and some have even added their own twist to the design. Darton’s Equaliser cable system is a great example of how manufacturers are developing the modified twin cam to create bows that are easier to adjust and tune and offer even more stability and consistency.

Modified twin cams are hugely popular with archers as well, due to their low maintenance and high arrow speeds. They also produce very low levels of hand shock when compared to other cam systems, this makes the bow more comfortable to shoot and helps deliver perfect arrow flight. You can find this cam system on the PSE Dominator Duo, Mathews TRX and the Hoyt Altus bows.

A decade ago every manufacturer fought hard to promote their favoured cam system. The cams on a bow could even be used to identify the brand. Whether it was a Mathews Solo Cam, a Hoyt Cam and a half or a Bowtech Binary system, each manufacturer stuck with their chosen design.

Companies are now taking a more pragmatic approach to bow technology and most bow ranges utilise nearly every cam system available to ensure each compound performs at its best.

Over the years cams have matured from the simple round wheels found on the very first compounds, to the super efficient and adjustable versions we see today and it’s the demand for faster, easier to shoot bows that’s helped to drive this development. In reality the function of a cam hasn’t changed in 60 years, so when choosing your next bow try not to be influenced by the current trends and hype and go for a cam system that feels right for you.

The anatomy of the cam

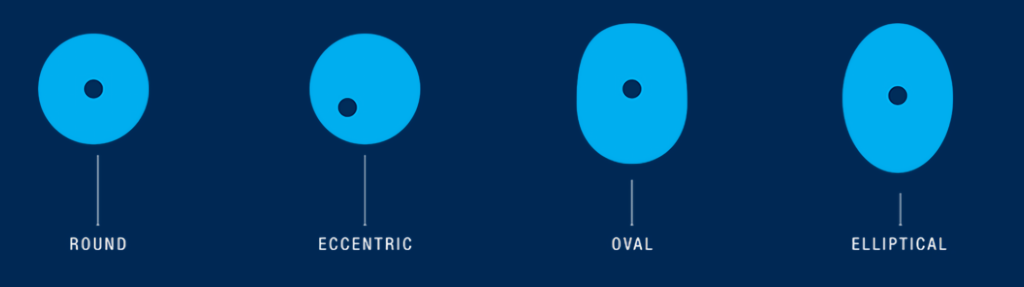

Profile: Round cams, eccentric cams, oval and elliptical cams – different profiles transfer energy into the limbs at different rates. More round-shaped cams tend to be easier to draw due to a smoother draw cycle with less time spent at peak weight, but as a consequence they often produce slower arrow speeds. Whereas more eccentrically designed elliptical cams produce faster arrow speeds by increasing the amount of time spent at the bow’s peak weight during the shot cycle. This makes them feel harder to draw and more aggressive in the shot.

Let–off: This is the amount of weight held at full draw given as a percentage. For instance, an 80% let-off will mean you are holding 20% of the bow’s peak draw weight. The amount of let-off a cam provides is largely down to its design and where in the draw cycle the stops are placed. This used to be fixed but recently manufacturers have acknowledged the benefits of being able to easily change the let-off by either switching a module or changing the position of the draw stops, allowing you to fine tune the bow’s holding weight.

Cam wall: The wall on a compound bow is the point at which the set draw-length is achieved and the cams stop rotating. Depending on the design of the stop, the wall can be either hard with no give at full draw or soft where you can pull a little into the stop. The feel of the wall is usually a fixed feature of the cam. However, it’s now becoming more common to have an adjustable wall allowing you to change the feel of the bow at full draw.

Valley: This is the final part of the draw cycle where let-off is achieved and the cams hit the wall and stop rotating. Depending on the design of the cam you can either have a short or long valley. A shorter valley will give the bow a snappy feel, as there is little travel between full draw and peak weight, whereas a longer valley will have a more relaxed feel at full draw.

Draw length: Having a set draw length is common to all cam types, the differences come in how that draw length is adjusted. Some cams offer a sliding adjustment module while others require you to replace the module entirely and sometimes even the whole cam in order to change the draw length.