A very short history of long distance shooting. By Jan H Sachers.

Targets have changed a lot throughout the history of archery. From birds to butts, from boards to bosses, archers everywhere have always proven very creative when it came to the question what to hit.

Of course animals have been targets right from the beginning, and sadly, humans too. But for probably just as long, people have practiced one form of archery that doesn’t need any target at all.

Shooting for distance, or flight shooting, is not only one of the oldest forms of archery. It is also the most simple one – all you need is your bow, an arrow, and a bit of space.

And it is a brutally honest discipline: When you loose an arrow at roughly 45° angle into the air, it will immediately and remorselessly betray a sloppy release, unmatched spine, unbalanced shaft, or any other shortcomings.

Shooting an extremely light arrow over the longest distance possible is also a good indicator to measure the performance of a bow. How much energy stored in the limbs is actually transferred to the projectile?

Can the construction handle the stress of (repeatedly) performing a shot that is almost identical to dry-firing? Many traditional bowyers today enjoy the challenge flight shooting provides, and they like to test their materials and constructions to the max – particularly if trying to discover and recreate the secrets of famous flight shooting bows from the past like those of the Ottomans.

But let’s start at the beginning. When was the first ever flight shooting competition held? No one can say with any certainty, but it likely happened shortly after the invention of the bow itself, some 20 to 25,000 years BC. ’I wonder how far this arrow will fly!’ or ’Let’s see if it really flies farther than your spear!’ or even ’I bet you this mammoth steak you can’t shoot across the river!’ – curiosity and competition have always been powerful motors for discovery and innovation.

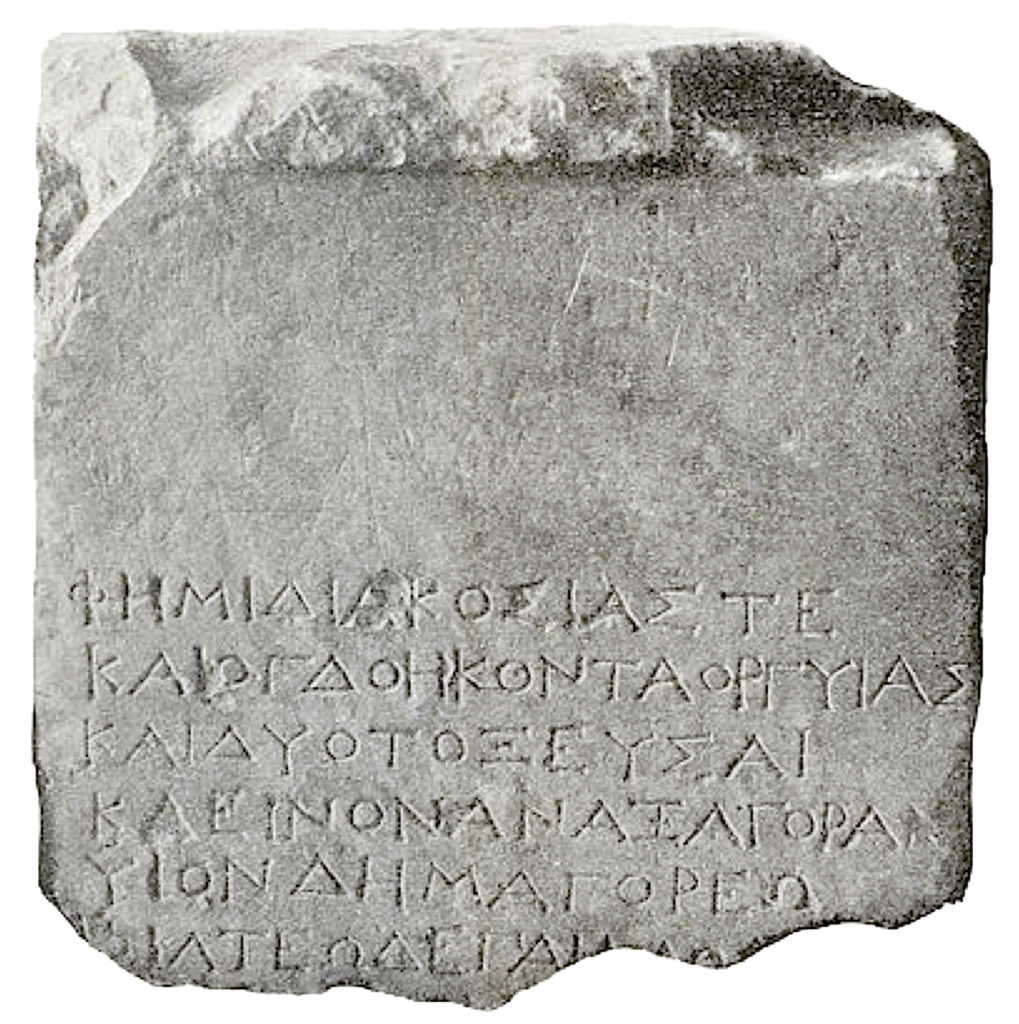

However, the oldest clear evidence of some form of flight shooting competition is an inscribed stone monument from the Greek settlement of Olbia near the Black Sea. It is variously dated to the Classical or the Hellenistic eras of Greek history, i.e. the 5th to 3rd centuries BC, and it reads: ’I proclaim that the famous Anaxagoras, son of Demagoras, shot 282 orguias with his bow.’

The ancient measurement is usually translated as ’fathom’ and in Byzantine times measured 1.87 m. So 282 orguias would equal roughly 522 m, or some 570 yards. This is quite a remarkable distance, which suggests that a rather powerful composite bow was used. And it was apparently deemed worthy enough to be, literally, set in stone. Unfortunately, this record remains the only evidence of such achievements for a very long time.

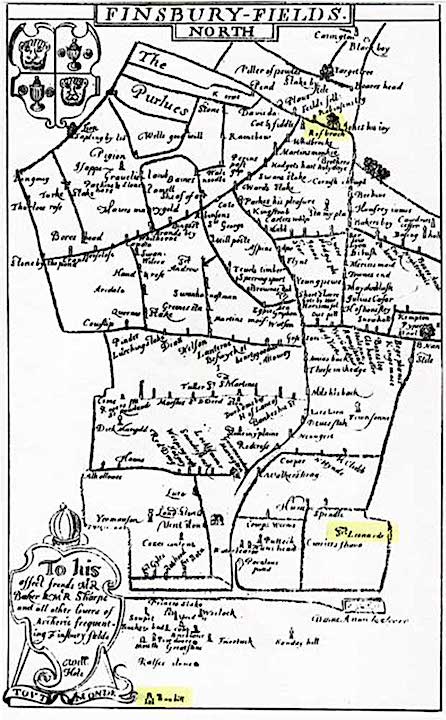

In medieval England archers practiced clout shooting, and shooting at the marks. In both disciplines the goal was to shoot arrows as closely as possible to a fixed mark far away. The clout was a piece of cloth, usually of some 18 inches in diameter, pegged to the ground at a distance of 160 to 240 yards.

The marks could be any natural or artificial monument, like columns of wood or stone, spread out over a vast area, and shot at from varying distances. The famous Finsbury Fields (est. 1498) in London once had 194 marks laid out over 11 acres of land to be shot at from 130 to 345 yards, according to a 1594 map. Clout is still widely practised today.

In 1542 King Henry VIII. issued a statute that ’no one under 24 shall shoot at any mark of eleven score or under with any prickshaft or flight under penalty of six shillings and eight pence’.

We do not know how this flight arrow was defined, or what set it apart from the standard, the livery, or the bearing arrows. Being used for great distances, it can be assumed that it was lighter than the others, i.e. cut from a lighter wood, and probably had shorter fletchings, which would in turn necessitate a lighter tip in order to fly straight.

Young men in their fighting prime were expected to deliver aimed shots at more than eleven score, or 220 yards, using their regular, heavy military projectiles. In experiments described by Strickland and Hardy, a replica of one of the longbows found on the Mary Rose of 150 lb draw-weight was able to shoot a 53.6 g arrow 360 yards (328 m) and a 95.9 g a distance of 272 yards (249.9 m).

In 2015 Joe Gibbs of the English Warbow Society shot 306 yards (279.8 m) with a livery arrow of 63.5 g, using a 170 lb longbow of Italian yew made by Ian Coote, and a 965 grain standard arrow 311 yards (284.37 m). In the 16th century, prizes were also awarded for distances shot with the lighter flight arrows: Eight pence for 20 score (365.76 m), 12 pence for 22 score (402.34 m), and 20 pence for 24 score yards (438.91 m).

As impressive as they are, these distances pale in comparison to the achievements in Turkey. The Ottoman Empire (ca. 1299-1922) was famous for its archers both on foot and on horseback, who played a crucial role in its enormous expansion during the 14th to 16th centuries.

But as in England, bows and arrows then fell out of favour as weapons of war and were replaced by firearms. Archery turned into a sport, and a national pastime. Every major city, and many minor ones, had at least one archery range, or ok meydan (literally: arrow field).

Some of them had an ’archer’s lodge’ (Okçular Tekkesi) attached to it, complete with libraries, dormitories, museum, and offices. Ottoman archers practiced target archery, usually at long distances of 90 to 265 m.

But by far the favourite, and most prestigious, discipline was flight shooting. On the shooting line, which was usually marked by a small stone, or column, social status didn’t matter much, and sultans shot next to officials, merchants, and craftsmen. There was, however, a hierarchy among the archers.

A novice had to practice until he was able to reach at least 900 gez (594 m) with a pişrev arrow, and 800 gez (528 m) with a . Only after these achievements had been witnessed by at least four officials – two at the shooting line, and two at the required distances – was his name recorded in the lodge’s or club’s register, and he was honoured with a graduation ceremony.

Records were also carefully noted in the registration books, some of which have survived. The highest distance known was shot by one Tozkoparan Iskender in the early 16th century with an astonishing 1281.5 gez (845.79 m). According to the surviving entries, distances of 800 m and more were not uncommon.

Record holders also had stone monuments on the archery range erected in their honour, with a poetic inscription detailing the archery’s name, the distance shot, and the date.

Several hundred of these target stones existed at one point, but most have now been removed, stolen, or destroyed due to changes in the urban landscape, and there are now just a handful scattered around modern Istanbul. One surviving example from 1789, now standing in front of the city’s Military Museum, bears a poem composed by Sultan Selim III which translates:

‘God blessed. Hüsameddin Ağa, good chief coffee maker of the sultan,

who achieved his target.

He took his bow and made an effort to succeed,

although he did not practice enough this winter …’

For some archers, flight shooting was more than a mere sport, or pastime, they were obsessed with it, constantly waiting for the right wind, the perfect conditions to perform the perfect shot. Like one man who – according to a well-known anecdote – was on his way to bury his son, when finally the north wind he had long been waiting for began to blow. The man hurried to the archery range, leaving his son’s burial to his relatives, and with tears in his eyes, shot a new record.

In 1795 Mahmoud Effendi, secretary to the Turkish Ambassador in London, shot a 25.5“ flight arrow 480 yards (which would have won him the 20 pence in the 16th century), to the great amazement of Thomas Waring and other notable British bowyers and archers present, as Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey relates.

The secretary however excused his ’mediocre’ performance with both himself and the bow being out of practice, and confirmed that the best Ottoman archers were able to surpass 800 yards. Payne-Gallway himself reached 367 yards under controlled conditions on 7 July 1905, and up to 421 yards in private practice, with a Turkish bow, and he mentions 340 yards as the farthest verified distance shot with an English longbow by one Mr. Troward in 1798.

At an archery contest held on the beach at Le Touquet, France, renowned archer and collector Ingo Simon (1875-1964) shot an arrow 475 yards (434 m) using an old Turkish composite bow with an estimated 100 lbs. draw weight.

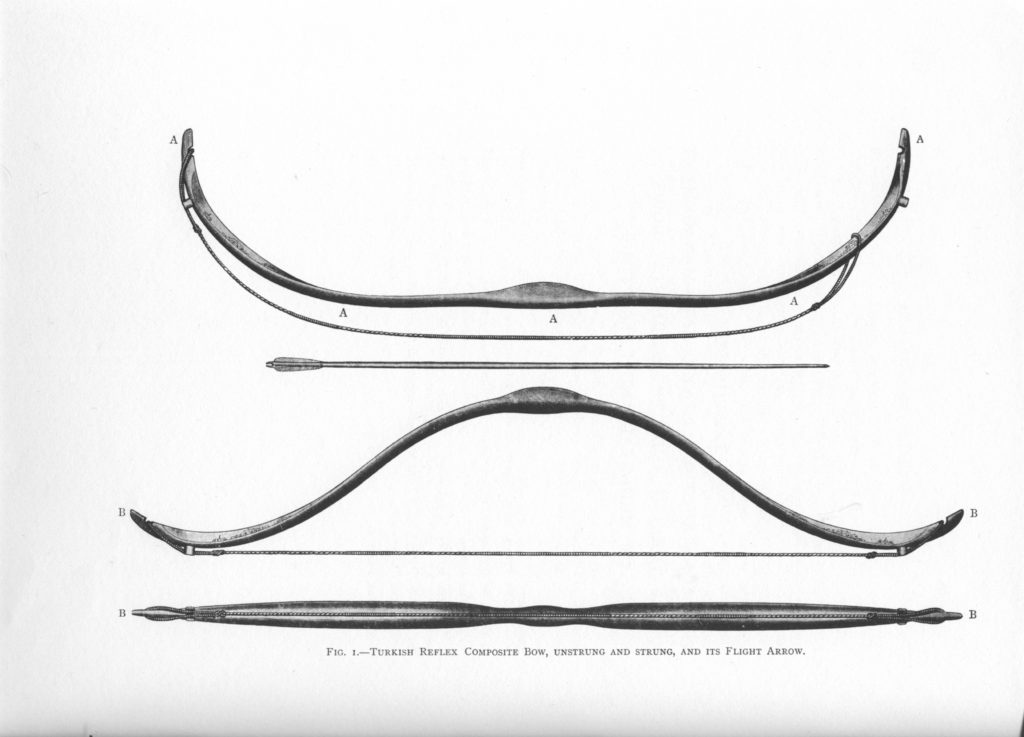

Turkish composite bows are works of art, and renowned for their capacity to store energy in their relatively short limbs. But just as much care and attention was given to the arrows. Ottoman flight arrows are among the finest examples of the fletcher’s craft.

Usually made from lightweight wood, with a tapered shaft, they were equipped with small points carved from bone, and often fletched not with feathers, but pieces of parchment in parabolic shape no longer than one or two inches.

The length of the shaft was often no more than 24 inches, and in order to still draw the composite bow to the max, a siper was used, a concave piece of horn or tortoise shell attached to the back of the bow hand.

Until the advent of new, synthetic materials in the 20th century the composite construction of horn belly and sinew backing on a wooden core remained the most effective way to build a bow, and the Turkish or Ottoman design proved one of the most successful.

Since the 1950s flight shooting gained new popularity particularly among bowyers who sought new ways to improve the design and effectiveness of their bows.

Recurved limbs are derived from several thousand years of composite bow development, and in order to shoot shorter arrows with full draw, many 20th century bowyers like Harry Drake experimented with various forms of overdraw, effectively copying the Ottoman siper from the 17th century.

Today, the flight shooting scene is an international community with regular official and unofficial competitions throughout the wold. The largest gathering, recognised by World Archery, takes place each year on the Bonneville salt flats in Utah, USA and offers over 100 different categories in which world records can be won.

The current record with an English longbow is 412.82 m, shot by Jószef Mónus from Hungary in 2017, while Ivar Malde from Norway achieved 566.83 m with a Turkish composite bow in 2019.

Comparing these distance with those achieved by the historical archers, it would seem that despite several centuries of advances in science, materials, and bow building technologies, we are still quite a long shot away from matching or surpassing their excellence.

Turkish flight bows

The Asian composite bow made of wood, animal sinew, horn and glue perhaps reached their technological apex in the middle ages. Specialist Turkish flight bows, or menzil, were slightly more crescent shaped that the boat-shaped war bows, and between 90 and 160lb in draw weight.

A wooden core, a kind of skeleton, gives the bow its profile and serves as a glueing surface for a sinew and horn. The back of the bow that faces tensile forces when in use is covered with sinew, a material which is more resistant than wood to that type of stress.

The belly is compressed as the bow is drawn, and on the surface, horn gives support to the wooden core. All the materials are glued to each other using collagen-based glues derived from animal tissues or fish bladders. The long drying and seasoning times meant that bows took (and still take) up to three years to make.

Over 30 separate pieces of horn were used per bow, and binding the strips to the wood surface correctly was vital, as both materials had to act as one under the huge compressive forces. To increase the glue surface area, both strips and wood were scratched with parallel grooves using a comb-like metal tool called a tasin.

This article is part of Bow’s flight archery issue. Subscribe to Bow here!

Are there records from possibly the forties & fifties on competition? I have a great Uncle that I remember being told he held records for distance accuracy. His name was Curtis Hill, and he was from Kettering, Ohio