Kristina Dolgilevica looks at an underrated element of form

To ‘follow-through’ means to bring an action to its conclusion or finishing position. If we consider the process of a pitcher throwing a baseball, we see that the follow-through consists of the athlete continuing to move the propulsive extremity (and the whole body) during and after the ball is released, thus controlling the trajectory of the object and adding power and velocity to it. It is the basic principle of mechanics that when an object is propelled with much force, the throwing arm needs to decelerate due to the forces exerted onto the joints during motion.

Imagine if the pitcher decided to freeze in mid-air and let the ball leave their hand without ‘sending’ it along a chosen trajectory in that moment. Most of the force that would have accumulated during motion would be contained within, or absorbed by, the propulsive extremity and the body.

This would risk instant injury, or contribute to a future one. Again, consider a punch in boxing. In a punch thrown with the intention of penetrating the pad, the power transfers and is absorbed, but a punch thrown with the intention of merely connecting with the pad surface results in the kinetic energy being retained by the fist or travelling back up the arm.

A similar principle applies when sports equipment is used, as it acts as the extension of the body. In the above scenarios, the power is generated within the body and transferred to the object instantly. Thus, one of the key functions of follow-through is to prevent injury.

Follow-through in archery

The same principle applies to archery, though the way in which power is generated and released and the constraints of the equipment are different in nature from these examples. Here, power is experienced in the form of resistance, which the archer must hold and maintain for some time with the help of isometric muscular contraction.

For the correct archery follow-through to take place, an archer needs to understand the physical demands of their sport. It is often described as ‘the maintenance of a position until the arrow clears the bow’. This definition is correct, but it is incomplete since it focuses on the archer’s posture and does not convey the dynamic nature of the follow-through motion. It takes milliseconds for the arrow to clear the bow, and technically it may seem like all an archer might need is a quick enough release.

However, long-term consistency can only be achieved via a good biomechanically efficient shot process, which promotes simplicity and effortlessness of movement. In practice, however, the opposite is often observed across the shooting lines, with some archers going into physical battle against the bow.

Archery is a fine-motor sport that demands repetition and consistency in all its aspects. The aim should be to develop a certain ‘feeling’ of the shot – this will be a smooth technique that, once achieved, will show in the way you follow-through. Thus, the follow-through shows us the result of our shot process.

It can be analysed internally by the archer, or externally by a coach or observer. It serves as a technical aid, helping archers develop, improve and automate a good release, and assists correct and constant expansion. It is an excellent mental aid, helping the archer’s concentration and focus. Think of the follow-through as something constant, continuous, balanced and natural.

A follow-through happens because of back tension, expansion direction, power balance and the regulation and timing thereof. It is not a stand-alone movement; it is a continuation of expansion, a natural reaction to the release.

No two follow-throughs are identical, but without a good one the shooting process can become complex, difficult to replicate and inconsistent; with one, an archer can turn target accuracy into precision. To develop a good follow-through, you must walk your way back to the moment you fix your posture – back to square one. Any interferences or inconsistencies during the process will affect the outcome.

If you want to achieve a good-looking follow-through, there is only one way to do it: through learning one clear shot process, introducing gradual digestible changes with lots of regular practice. It is not humanly possible to replicate the same process every time – the state of mind and body are in constant flux.

We can only do our best to get close to the desired ‘feeling’ at any given moment. An archery shot is as delicately balanced as a house of cards – take one card out and it will fall apart.

The science bit

A few considerations for the archer who wishes to finish their shot well. Firstly, once set, body posture and head position do not change throughout the shot sequence. The archer should assume correct posture at the very start.

There should be no change in anchor during expansion. A good hook should be established at the beginning, and the archer must make sure they do not draw with their arm; it is a good idea to teach the archer to focus to draw with the elbow as a guide, shifting attention away from the idea of consciously releasing with their hand.

Many archers begin to readjust their hook as they come into anchor; this introduces unwanted tension in the hand and/or forearm, ruining the release. The follow-through is a continuation of your expansion, during which back tension and expansion should not change.

Special attention must be paid to shoulder alignment. If the archer experiences issues with alignment, it will not be possible to feel the correct back tension, nor will it be helpful in creating a proper expansion line.

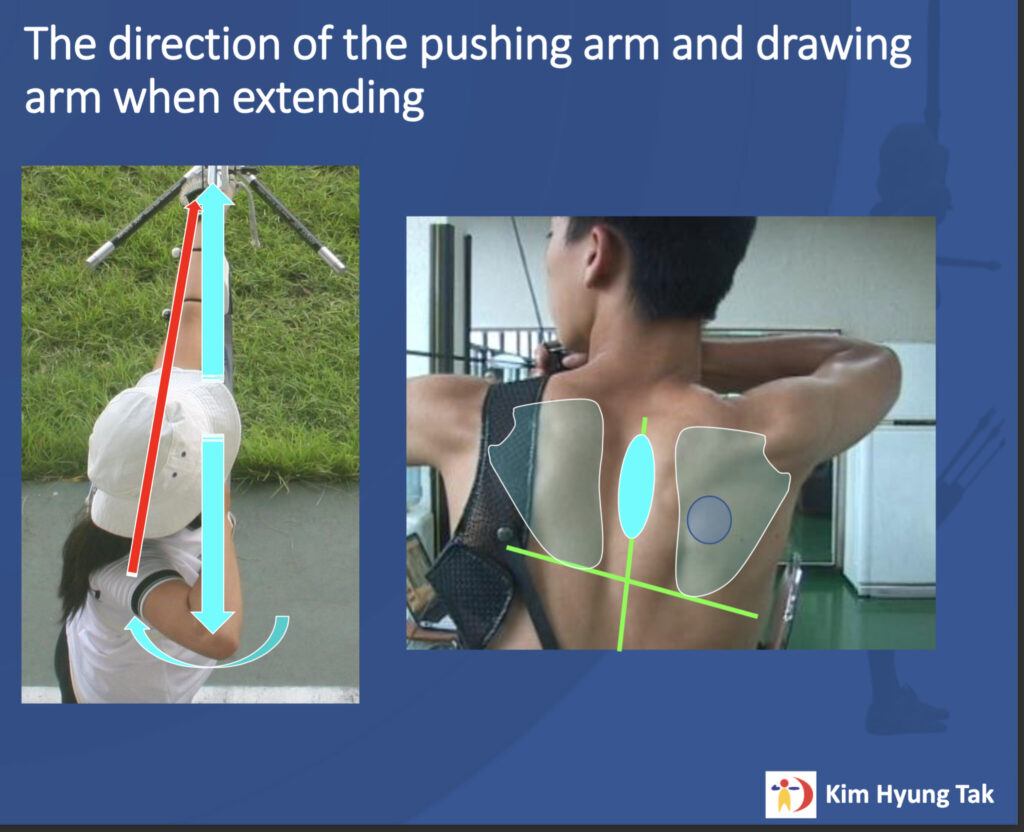

Set-up is a pivotal moment because it is where an archer establishes the draw force line. Expansion forces and direction depend on that, as they will build on the balance of powers established during set-up. The archer must create a balance between the draw and forward-resistance of the bow arm. If no balance is established, the archer can expect issues in alignment and shot.

It is important that the drawing speed should be smooth, controlled and constant, drawn straight to anchor. Drawing too fast risks introducing unwanted muscular tension – too much too soon prevents proper expansion.

The centre of expansion balance should be located between the two scapulas, and equal power balance should be established between the pushing and the drawing arms. Once the archer has arrived at anchor, they need to ensure that it sits firmly and is the same every time, as changes will affect the draw length. If the anchor is barely touching, the bowstring will move. Proper expansion cannot take place, as the anchor is the point of balance from which expansion is facilitated.

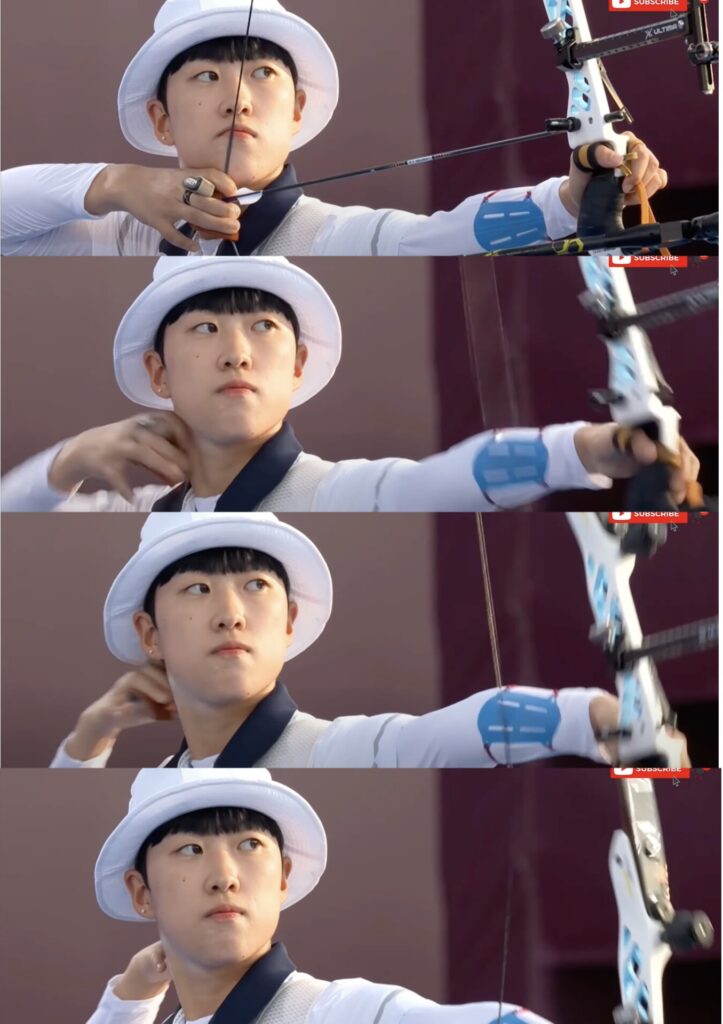

Watching the bowstring on the chest of the archer is perfect for observing their expansion. If proper back tension is used and the correct expansion balance and direction are achieved, the string on the chest does not move.

Expansion should be invisible to the naked eye, constant and balanced throughout, and must follow the same direction on each respective side, especially during release and follow-through. Should the archer experience any major internal power-balance shifts or alteration during the process, they are expected to result in suboptimal performance.

If the draw arm is not sufficiently drawn or there is loss of power, the elbow will creep and the string will move forward. If the bow arm shoulder creeps up, or if the bow pushes back because of insufficient power, the string moves back.

In both instances, expansion balance and direction are lost, resulting in technical collapse. If the archer tries to rectify the situation without letting down, they will likely experience extra stiffness or muscular engagement that results in exaggeration of the expansion.

In both cases, the arrow will hit left-right. It is a good idea for the archer to learn how to stay relatively loose in the upper body, building power gradually from the ground.

General: Considerations for beginners

The only time an archer can view the follow-through as a separate part of the process is at the very beginning of their development when they are introduced to the steps of shot cycle. It is useful to think of the follow-through as part of the release, introducing the archer to the concepts of back tension and expansion early in the process.

The instruction may be to move the fingers along the neck (or face for barebow), no more than 3cm back, following the expansion direction line, matching the forward resistance of the bow arm. Even if the movement looks fragmented at the start, this will begin to guide the archer’s attention away from the fingers and their hook, shifting physical and mental emphasis onto their back. Using a non-rigid back tension trainer with an elastic element will allow the archer to continue to follow-through until the natural full stop.

Rigid shot trainers do not truly translate the required ‘feeling’ and often restrict the movement, forcing them to freeze or tense up unnecessarily. Introducing the finger sling at the start will help the novice archer develop the ‘feeling’ of their shot in their bow arm. With practice, over time these early interventions will eliminate many future mistakes.

Archery mastery requires an exceptional degree of self-awareness from the archer. It is up to the coach to find a way to help explain what they mean by back tension, expansion direction, draw force line and so on.

It is also up to the archer to help themselves enrich their understanding of the experiences the human body goes through. Do all that is possible to better understand your physical and mental states.

Motor Skill: Why we need a consistent follow-through

Dynamic sports are tactically and strategically more complex, require quick reactions and often multiple decisions to be made during one particular action. For example, a football player kicking a ball while moving across the pitch moves both across the space and in space.

Here, multiple follow-throughs are possible because there are many ways to kick and his task is to be accurate, not precise. Archery is all about precision but is tactically and strategically less complex, with a shared objective in both practice and in tournament.

The task is to recreate the same process to the same outcome – hit the target downrange. Decisions may be situational, for example related to compensating against the wind. There should only be one same way to follow-through to be precise.

To be able to retrieve a learned skill unconsciously and automatically at a pivotal moment during performance requires motor memory. The goal is to be able to go through the process without thinking about it. Before a motor memory can be stored in our brain, it must be learned and automated via long-term practice.

A professor of engineering at Cambridge University, Dr Franklin, along with neuroscientists D Wolpert and I Howard, designed a joystick-guided experiment, looking at whether a change of follow-through might have an effect on the speed and accuracy of learning a task.

Volunteers were divided into two groups. Each had to guide the joystick toward a primary target, then the secondary follow-through target. For the second group, the follow-through target was randomised and a force field was added to the joystick, making it harder to steer. They therefore had to learn two different ways to follow-through.

When the task is about precision and the follow-throughs during practice become random, the brain may get confused as to which motor memory is being recalled. Each movement requires a unique motor memory and plenty of deliberate practice, even when the movements are similar in nature.

For example, the use of a tennis racquet may be similar to the one used in badminton, but each will have its specificities and require a unique memory. That is why you don’t shoot your friend’s bow as well as your own.

Their study concluded that those who only had one follow-through direction learned faster and achieved greater accuracy. Check your shot process, walk back, correct gaps in your skill and follow-through in the same direction.

Final note

Remember that poor form and injuries can be a result of inappropriate equipment selection. Equipment that is too powerful or too heavy will prevent you from achieving proper alignment; muscles work harder, fatigue is introduced quicker and your process will be inconsistent and inefficient.

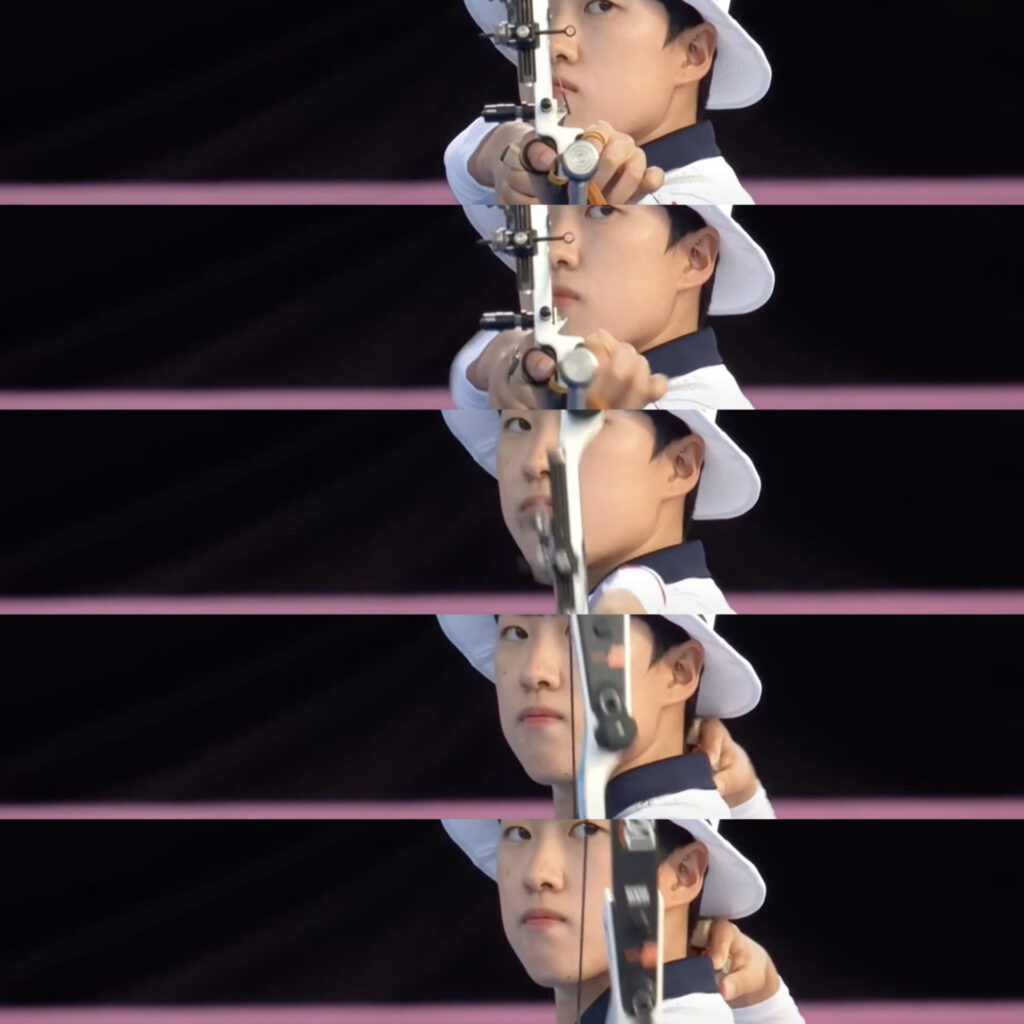

The opposite is desired if you wish to achieve good form and a good-looking follow-through. South Korean archers are the best example to watch for form, and their follow-through, unique to every archer, is useful to observe.

The reason why their shot looks effortless is not that they use light bows or shoot 2,000 arrows per week. They do not use the muscles they should not and only shoot bows they can handle.

The focus should be on a biomechanically efficient shot process that relies on gravity, bone alignment, understanding of expansion power and direction, and engaging in warm-up protocols based around mobility training.