The essentials for keeping your bow arm strong.

Keeping the bow arm stable is vital in recurve archery, but it’s surprising how quickly the strength can drop off – especially if you’ve been out of the game for a few weeks. In this article, archers and coaches Naomi Folkard and Gunther Kuhr let you know how to keep things strong.

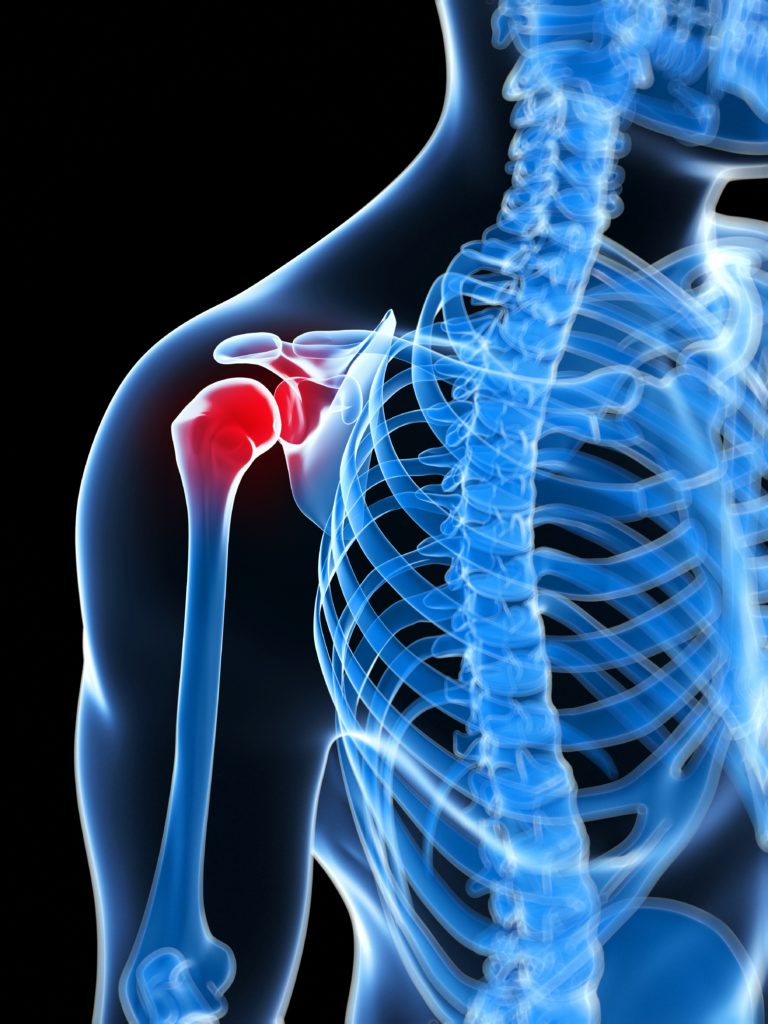

The shoulder is one of the more complex joints in the body. It’s sometime likened to a golf ball on a tee, but the ground on which the tee is sitting in can move!

It’s worth spending a little time looking up exactly how the shoulder works; the humeral head sits on the glenoid which is formed out of the outside corner of the scapula. Bear in mind that the scapula itself is able to move in any direction and has not got a fixed resting position.

The shoulder is more commonly referred to as the “shoulder complex” rather than a joint because it comprises of thirty muscles, six ligaments, four major bones and tendons.

It has the potential to be one of the most unstable joints in the body: there is a delicate balance between the mobility required to perform daily and more extreme tasks (sports and manual labour) and the stability required to power and stabilise the arm.

Instability easily results in pain and injury due to the tiny spaces for the tendons within the shoulder structure. The requirements of the front arm in archery include achieving alignment; for injury prevention this is best done early in the shot without much stress from the draw weight.

As well as alignment, the arm needs to raise, and the elbow should rotate. At full draw the front arm needs to be stable and adjust for the wind or and instability, and the shoulder needs to resist the bow both at full draw and on that moment of execution when the bow pushes into the hand.

Stability within the shoulder comes from both static and dynamic stabilisers. The static stabilisers are the vacuum effect, labrum, capsule and bones, while the dynamic stabilisers are the muscles and proprioception.

For archery we aim to have the bones in the bow arm and shoulder in a straight line which naturally bring stability and strength. Elbow rotation adds to this stability by gently engaging muscles at the back of the upper arm, however if the elbow is locked out and rotated so hard that the muscles are overly tight the advantage of stability is lost.

Proprioception uses the muscles to continuously adapt and stabilise against perturbations. For example an archer must adjust output of muscles quickly based on the “position of the arm and information taken from physical feelings and visual cues etc. processing that information and reacting in the form of movement in the muscles.

Since the muscles are involved in stability, strength plays a very prominent role. An archer must be strong enough to do the action with ease. By this, I mean they must have plenty of activation capacity left over in order to make adaptations.

The muscles cannot be working at 100% because there would uncontrollable shaking, creating instability rather than inhibiting it. On the other side of the coin I’ve had some huge strength and conditioning coaches have a go at archery, and they shook a really surprising amount because they were unable to switch off muscles when didn’t need to be used at 100%.

The more experienced archers should generally have better proprioception and that proprioception should be more automatic, therefore there’s an argument that we can improve our proprioception and stability through practice.

However there are more modern scientific ideas; we can in fact deliberately practice and improve our proprioception and stability by challenging stability both while shooting and by doing certain non-archery exercises in the gym.

It’s important to bear in mind that just as you wouldn’t start a weight or cardio training programme at a really difficult level, nor should you start proprioception training programme at a really difficult level.

People with hypermobility should consider refraining from stretching the shoulders as this can increase mobility even more and increase instability of the shoulder and therefore the injury risk.

The setting up of the front arm and elbow rotation has to be done differently and thought has to go into finding the technical solution for each individual.

To sum up: start easy with small challenges. Improved shoulder stability will help prevent injury, however the progression itself should also be sensible to avoid injury. Here’s how to do it.

Exercises while shooting

You can deliberately train in the middle of the field or on windy days, or try to shoot standing on a soft mat or balance boards. More advance archers might like to have a friend add instability to the front arm by tying a soft theraband around the wrist at a low tension and have your friend shake it very gently while you are at full draw from different directions – gradually build the difficulty here!

Non-archery exercises

Side planks of all variations are excellent: arm straight on an unstable surface, soft mat for instance or a ball or BOSU with feet on a chair, arm bent on swiss ball. Using a wobble stick in all directions is good. Try standing and falling push-ups onto a door or workbench.

Try Swiss ball roll-outs, and drop catches. An exercise that I’ve recently learned to improve my shoulder stability is the “Turkish Get Up”, which is also a great all round exercise. Look it up on YouTube and you will find great demonstration videos.

There is a seemingly unlimited number of exercises out there that can develop shoulder stability, just do some research – and start easy.

Naomi Folkard

Keeping it turning

Even beginners learn early on that the elbow joint of the bow arm is turned inwards towards the bow. But turning the elbow joint also is important for the stability of the bow arm at the moment of execution. Even the slightest movement of the elbow joint can be transferred to the bow.

Instabilities in the bow arm happens so quickly and can be so minimal that they are often only visible in video analysis. Yet they will lead to the bow being moved by several millimetres while the arrow is still in contact with the arrow rest, which will make a difference of centimetres – or worse – at the target end of the field.

Experience shows that a relatively small and even movement in the bow arm can still give rise to passable groups of arrows, but more stability in the bow arm is of course always preferable.

Learning to turn

The elbow joint is screwed in automatically by an experienced archer. Beginners have to consciously train screwing in first. Younger archers and children may not have the strength to hold the position. In this case, at least for the time being, it may be better to just find a position for the elbow which can be held as steadily as possible.

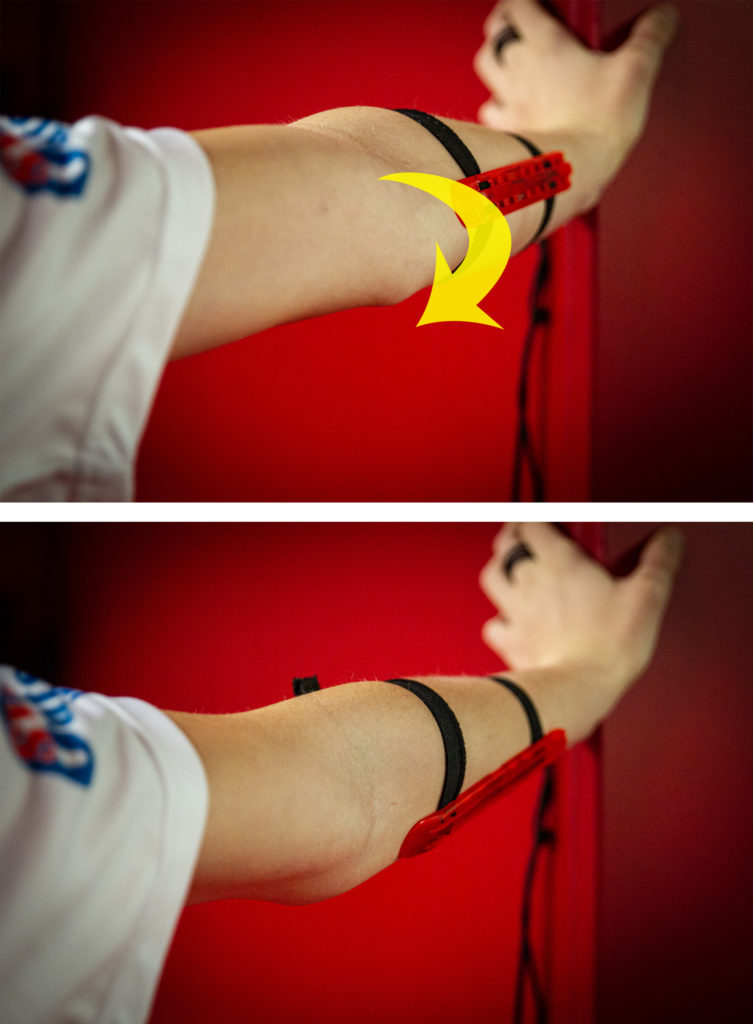

The usual easy way to learn the motion and train the muscles involved, without a bow, is to extend and place your bow arm with your bow hand at about shoulder level on a wall. Now lean against the wall, so that you feel a slight pressure.

Start now with the bow arm extended, turning the elbow joint again and again until you get the movement controlled. (Some archers use this as a warm-up). You should practice this with a bow too.

You should be screwing in the elbow joint either in the first position draw phase (i.e. before lifting the bow), or in the second position phase (i.e. after lifting and before drawing).

Whichever part of your cycle involves the elbow turning, it should be exactly the same each time, or you will never automate the process. It will take some time, and a lot of attention paid, to consciously attune yourself to feeling the strength in the holding position.

Technical help

Basic video analysis with your smartphone, with the yellow guides are on. This is the sports analysis app called “Coach’s Eye”.

An easy method to check the stability of the bow arm at execution is taking a video recording with a modern smartphone with a high framerate. Many smartphones now offer a slow-motion mode as standard.

The better-known analysis apps include “Coach’s Eye” and “Dartfish Express”. With these apps you can repeat the moment of launch, fast-forward and rewind and seen even the smallest movements. (Remember that movement in the movements in the one-millimetre range will have astonishing scattering effects over long distances.)

Apps can also offer on-screen line tools as aids to make small movements visible. It’s especially important to watch the stability here at the moment of launch.

In high speed recordings of the top athletes with a stable shooting technique, the elbow will remain absolutely motionless, and you shouldn’t start to see it move until the arrow has left the bow.

The fixed elbow joint brings you one step further in stabilising your shooting technique and it’s a vital biomechanical feature on the way to better shooting results.

Günter Kuhr

Twisting the elbow joint under stress is not recomended.