When archery became eccentric. By Jan H Sachers

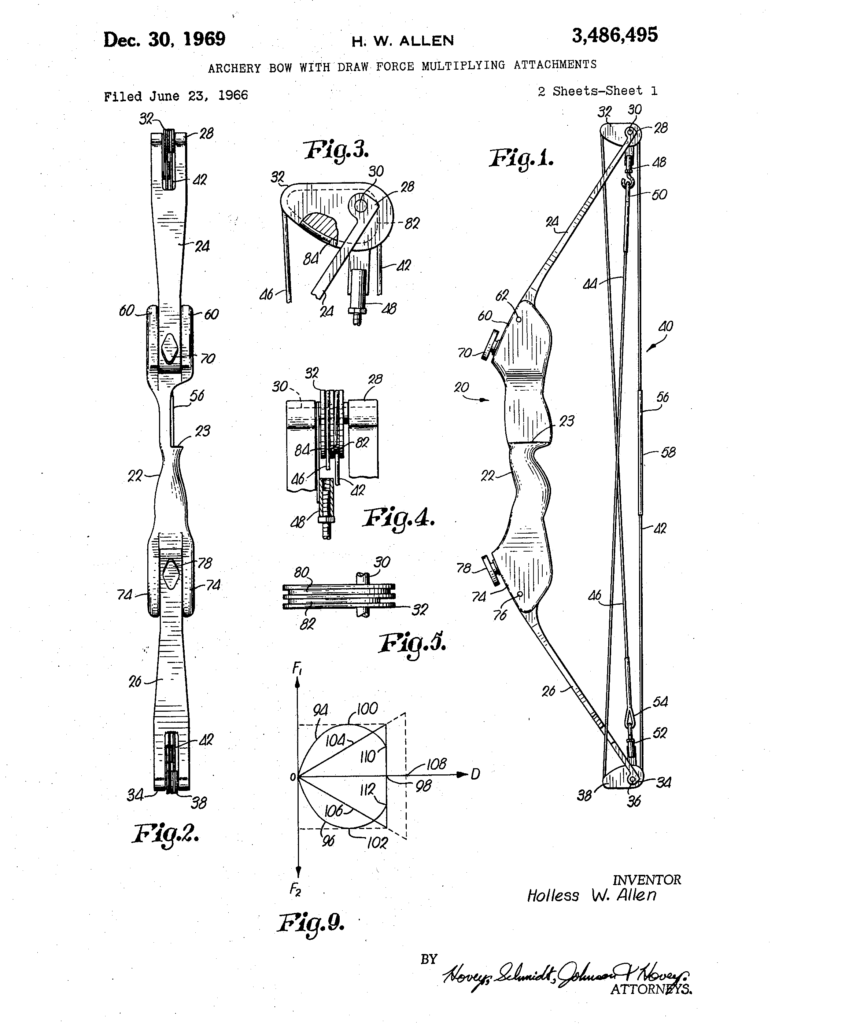

On 30 December 1969 the US Patent Office published patent no. 3,486,495 for an archery bow with draw force multiplying attachments. An inventor named Holless Wilbur Allen (1909-1979) had applied for it three years earlier, after spending much time experimenting with different designs in order to develop a bow able to store more energy and accelerate an arrow with greater speed, without the need for a longer draw or more force to hold the string in a fully drawn position.

In his application, he claimed that “the archer’s bow has not changed in basic design since the development of the long bow many centuries ago”, which is essentially true, even if the long bow had been in use for several millennia.

A bow works like a leaf spring, which is kept under tension by a string attached to both ends. Pulling the string bends the limbs, which store energy that is then used to accelerate the arrow upon release. The archer’s muscle work, which is applied slowly during the draw and stored in the limbs as potential energy, is converted into a rapid movement of the limbs during release, and transferred to the arrow by the string.

Changes and developments over the centuries mainly affected length, shape and profile of the limbs, as well as materials used. Apart from different types of wood – such as elm, ash and, most importantly, yew – laminates of wood, bamboo and fibreglass, which was already well-established in Allen’s time, sinew backings were sometimes used to increase efficiency.

Composite bows – with sinew on the back and horn on the belly – could be built shorter, and with varying degrees of reflex, without loss in draw weight or draw length (see Bow International 161). But they also made use of another physical principle.

The stiffer ends of the limbs, sometimes called siyahs, which point away from the archer when the bow is braced, start to act as levers during the draw. More energy is stored at the beginning of the movement, which means more force is required, but as soon as the string lifts off the limbs, the lever action makes it easier to pull.

Allen was looking for ways to increase this effect even more, so that the force required to hold the string at full draw was lower than the actual draw weight. Even if he did not mention this explicitly in his patent application, he saw his main target audience among the bow hunters, a huge market in the US, who would be able to aim at full draw for a long period of time with much less exertion.

He glued and screwed together his prototype – now on display at the Archery Hall of Fame and Museum in Springfield, Missouri – in 1966 after many years of experimentation. It has a long pinewood riser and short limbs laminated from oak planks and strips of fibreglass. The string runs crosswise through ellipsoid wooden cam discs mounted on eccentric axes at the tips.

This mechanism is often compared to that of a pulley tackle, but strictly speaking, this is only true for later commercial models with more than two wheels. Allen actually made use of the same lever-action principle that had made the short reflex bows of the Eurasian steppe archers successful for centuries. But replacing the long and stiff levers, or siyahs, which suffer great mechanical stress during the draw and add mass to the end of the tips, with his eccentric wheels or cam discs, fulfilled the purpose much more efficiently.

Another benefit of this construction concerns the acceleration of the arrow. With a conventional bow, the maximum force is reached at full draw, and energy transferred to the arrow decreases continuously from the moment of release until it leaves the string. With a compound bow, the exact opposite happens. The arrow accelerates slowly at first, then faster as long as the string keeps pushing, which reduces the archer’s paradox, and results in higher arrow speed and a lower trajectory.

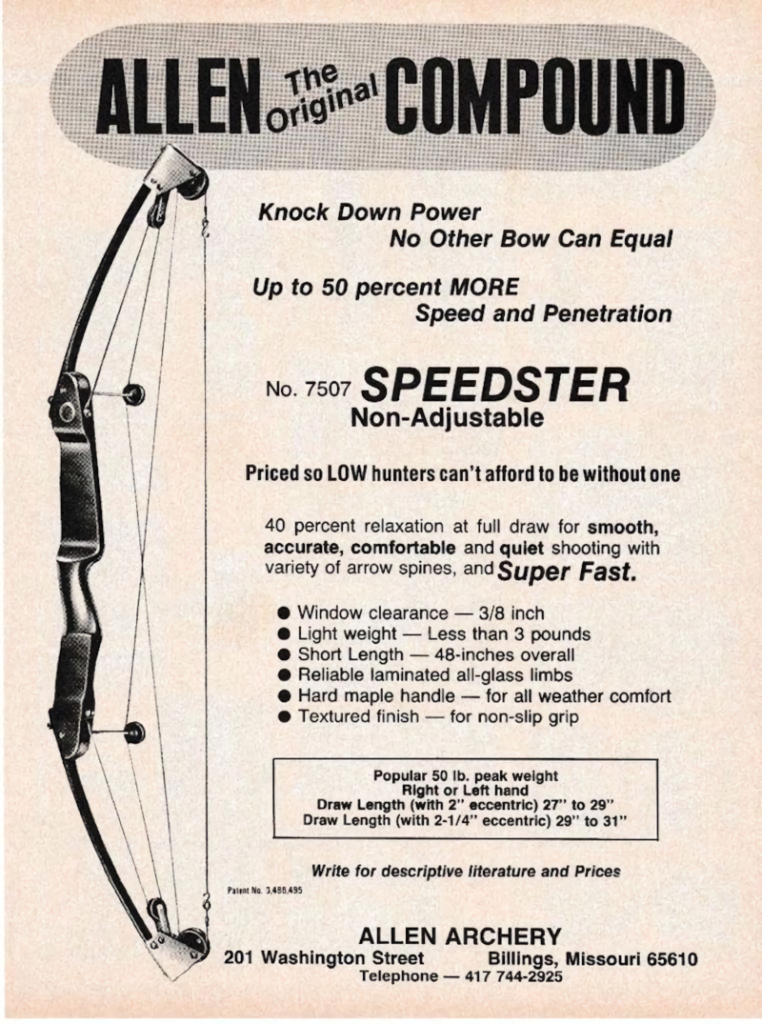

Having had his invention patented, H W Allen tried to convince established manufacturers to mass-produce his bow, but without success. His prototype looked ungainly and ugly. The let-off at full draw was only around 15% and the increase in arrow speed was only about 20% compared to contemporary recurve bows.

Eventually, Allen developed some models of his own. He sold them under the company name Allen Archery, albeit in relatively small numbers. Most of his bows deviated from his original design, featuring a string attached to the limbs, running through four or six wheels or pulleys. They worked like a pulley tackle, but did not look much better than his prototype and had to be readjusted a lot.

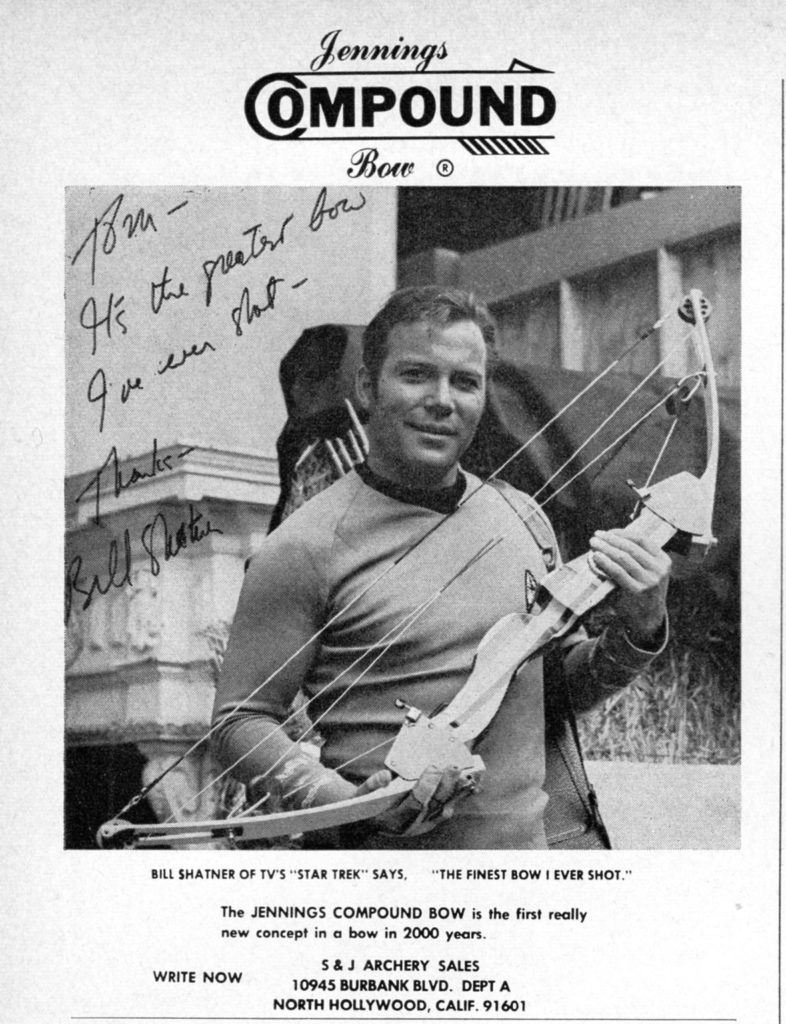

In 1972, Carroll Archery and Olympus were the only brands besides Allen offering compound bows, as they were now called. But then renowned bowyer Tom Jennings (1924-2013) became aware of this new type of bow, recognised its potential.

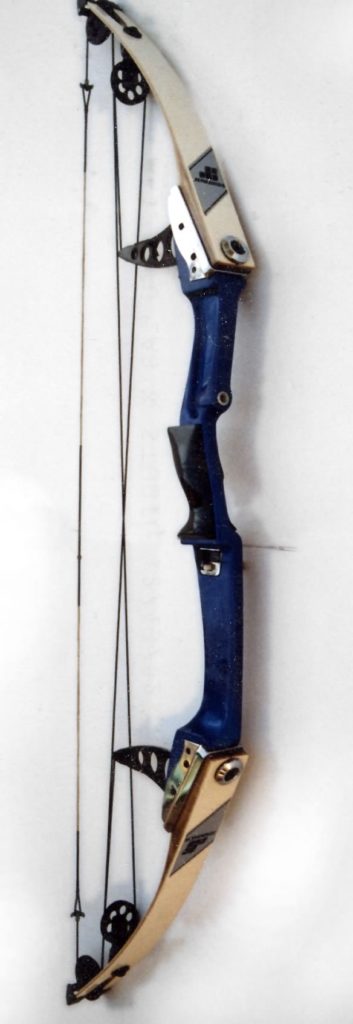

He immediately terminated the production of his own recurve bows and created the Jennings Compound Bow Corporation instead. His legendary Model T with two cam wheels and cables running from tip to tip “revolutionized the revolution”. It was easier to maintain, lighter and much more elegant than his competitors’ models. It became an instant success.

By 1975, Jennings sold 60,000 bows per year. Other producers joined the parade. Allen licensed several companies to use his design, including big players such as Precision Shooting Equipment (PSE), Bear, Martin, Browning, Pearson and Hoyt.

Allen and Jennings campaigned for compound bows to be approved for hunting and later target archery. Once they were approved, the success story practically wrote itself. According to Archery Digest, roughly 100 different models were available on the market in 1977, with only about 50 types of recurve bows. Within just 10 years, the compound had become the dominant class of bow in the United States.

While remaining true to H W Allen’s original idea, all manufacturers experimented with new concepts and materials, some more promising than others. Especially shape and attachment of the cam wheels were subject to frequent innovations and experiments. Alongside the twin cam bows like Jennings’ Model T, the first single cam compounds hit the market in 1975, with only one pulley at the top and a big cam wheel at the inflexible lower limb. This eliminated the need to keep two cam discs synchronised.

Limbs were generally laminated, or made of fibreglass alone, attached to the big, heavy wooden risers by various systems, which often failed. Early models tended to be rather long, because they were still drawn with three fingers.

Only when mechanical release aids were developed and approved for competition, did the bows became shorter, which was welcomed by the bow hunters. While most bows used forward limb movement, as had been the case for thousands of years, new designs had the limbs mounted more or less horizontally, which resulted in vertical limb movement, and a stable shot, but also a narrow string angle at full draw.

Many of the prototypes and some of the production models of the 1970s and ’80s appear a little eccentric to the modern eye. Some innovations like the one limb bow or the Penobscot design proved unsuccessful, but a number of these experiments led to new solutions that were later integrated in more conventional models, for example the split limbs, or twin limbs.

As foreseen by H W Allen, bow hunters in particular loved the new type of bow, and created a huge market that is still going strong. According to the 2015 survey by the Archery Trade Association (ATA), the majority of the 11.8million bow hunters in the US shoot a compound bow. Practically all manufacturers sell special hunting models, often in camouflage design.

When various archery federations approved of compound bows for target competition in the 1970s, they quickly dominated the fields, so that new rules and classes had to be added. World Archery (then FITA) first included compound archery as an individual discipline in the 1995 World Championships.

The target of four concentric circles of 80cm diameter is shot at a distance 50m, although it is occasionally mooted that this distance should be longer.

World Archery, as well as most national federations, now also have compound classes for indoor, field, para and 3D archery – although many 3D courses don’t allow them due to their longer range and higher penetration power.

The annual flight championships on the Bonneville Flats in Utah also have different classes for compound bows. The current record of 1,207.39m in the compound flight unlimited class was won by Kevin Strother in 1992. Curiously, though, it is roughly 15m shorter than the distance shot by Don Brown in 1987 with a conventional recurve bow made by Harry Drake.

Allen’s patent expired in 1989, and nowadays compound bows are produced and sold by a number of manufacturers all around the world. Today’s models are usually made entirely from modern materials, such as aluminium, fibreglass and carbon.

Exchangeable limbs and cams offer a variety of individual setups to make the system suit the archer perfectly. A typical let-off is now at about 80%, so that only 14lbs need to be held at full draw with a 70lb bow. Lightweight carbon arrows with five or six grain per lb can reach an initial velocity of up to 320ft/s (97.44m/s or 351.13km/h).

Compound bows are often used with additional equipment. Most common are a scope, frequently with integrated magnifying lens and spirit level, and a peep sight fixed into the string. Stabiliser rods are usually added. The string is pulled with a mechanical release aid hooked into a small loop at

the string.

Holless Wilbur Allen was able to witness the early stages of his invention’s success story, but died in a tragic car accident in 1979. Tom Jennings remained a passionate bow hunter all his life. He continued to push the development and improvement of his products. Chief among his most successful innovations are the adjustable cams, which allow for draw length and let-off to be individually customised.

They have become a regular feature on every compound bow by all manufacturers. His merits earned ‘Mr Compound Bow’ a place in the Archery Hall of Fame in 1999. His name has actually became more famous than that of the original inventor H W Allen, who was only honoured this way in 2010.

No other invention had greater influence on the world of archery than Holless Wilbur Allen’s archery bow with draw force multiplying attachments. Not only did his compound bow revolutionise the design and functional principles of this millennia-old hunting weapon, but it also initiated technical developments that resulted, among other things, in the now common use of ever the latest high-performance materials. But in an irony of fate, the pioneers and champions of the compound bow accidentally also started another successful archery movement.

After all, the renaissance of traditional archery with its wooden self-bows and home-made arrows began its life in the US of the 1980s as a grassroots protest against the modernisation and mechanisation of bowhunting, with its compounds, scopes, sights, release aids and space-age materials!

How many compound bows are made each year?