Reduce injury and increase flexibility – and that’s just the start. Kristina Dolgilevica shows you how

Defining mobility can be a little confusing. When you look up ‘mobility training’, you will come across the big ‘mobility versus flexibility’ debate. Many will refer to a wide range of static or dynamic exercises simply as ‘flexibility training’, leaving you wondering: are mobility and flexibility the same thing?

The answer is yes and no. How one defines the terms is largely dependent on the sphere to which the sports professional or speaker belongs. Some will use the terms interchangeably, some more specifically, to denote a precise mechanical function or property.

In this article, the terms are defined from the point of view of human kinetics (motion, dynamics) and are separate: ‘flexibility’ as the ability of the muscles and tendons to go through the range of motion (ROM) about a joint and ‘mobility’ as the coordination and efficiency of movement throughout the ROM of the joint, relying on the activation and coordination of neuromuscular action. The structure of the joint often dictates the ROM and affects the overall dynamics of the joint – its capsule, ligaments and tendons – and the muscle spanning it.

We can say that flexibility measures the capacity of a joint to move throughout its ROM. In an applied setting, flexibility training is often associated with muscular elasticity and passivity and can be described as the ability of the soft tissue (muscle, tendon) to stretch, lengthen and shorten around a joint without active muscular contraction: in other words, ‘sitting in a stretch’ and allowing gravity to do its work. (It can be an assisted stretch, for example, with a yoga block or someone helping you.)

As we age, our muscle tissue loses its pliability, leading to muscle-fibre degeneration, known as fibrosis. Coupled with connective tissue decline, it limits the flexibility of the tissue, resulting in the increase of joint stiffness and reduction in ROM. The purpose of flexibility training is to find your individual ‘stretch tolerance’.

Mobility, on the other hand, often refers to multiple joint coordination and is about competency, or how well a person can perform a controlled movement, or reach a certain position, without compromise. Mobility training is often associated with joint stability, articulation, strength and deliberate muscular contraction.

Some joints, such as the hip or the shoulder (the most flexible joint in the human body), provide for a greater ROM in multiple directions, while joints such as the ankle, the knee, the elbow and the wrist are classed as ‘fixed’, exhibiting lesser ROM, with less directional movement.

There are many exceptions and conditions related to abnormal workings of joints. These conditions can be developmental (occurring during puberty, for example), inherited or acquired (through an accident, for instance) and can be harmful or debilitating to athletic performance and quality of life if appropriate rehabilitation is not adopted.

The most common inherited condition is hypermobility, where joint(s) go beyond the normal range. The most common acquired condition is hypomobility, a connective tissue disorder where ligaments are shortened.

A common cause for that is lack of movement, a disease (arthritis, for example) or an injury. It is particularly important to notice these conditions at developmental stages (pre-pubescent, puberty), taking into consideration that growth spurts are likewise individual and will influence both the athletic performance of juniors and their individual physiology.

Medical and sports professionals advise against early sport specialisation and encourage instead a wide variety of sports activities to aid a more wholesome physical development through exercise, promoting a wider skillset.

There are two key factors that will affect the ability to develop and sustain mobility and flexibility: physiological (for example, age, sex, body composition, level of physical activity) and kinesiological (origin and insertion of muscle and tendon, joint structure and integrity and muscle CSA – physiological cross-sectional area – which deals with the muscle’s contraction properties). Some factors, such as physical activity or body composition, can be manipulated, while others cannot. All factors will affect an individual’s capacity for mobility and flexibility.

Overhead sports scapula and shoulder mobility

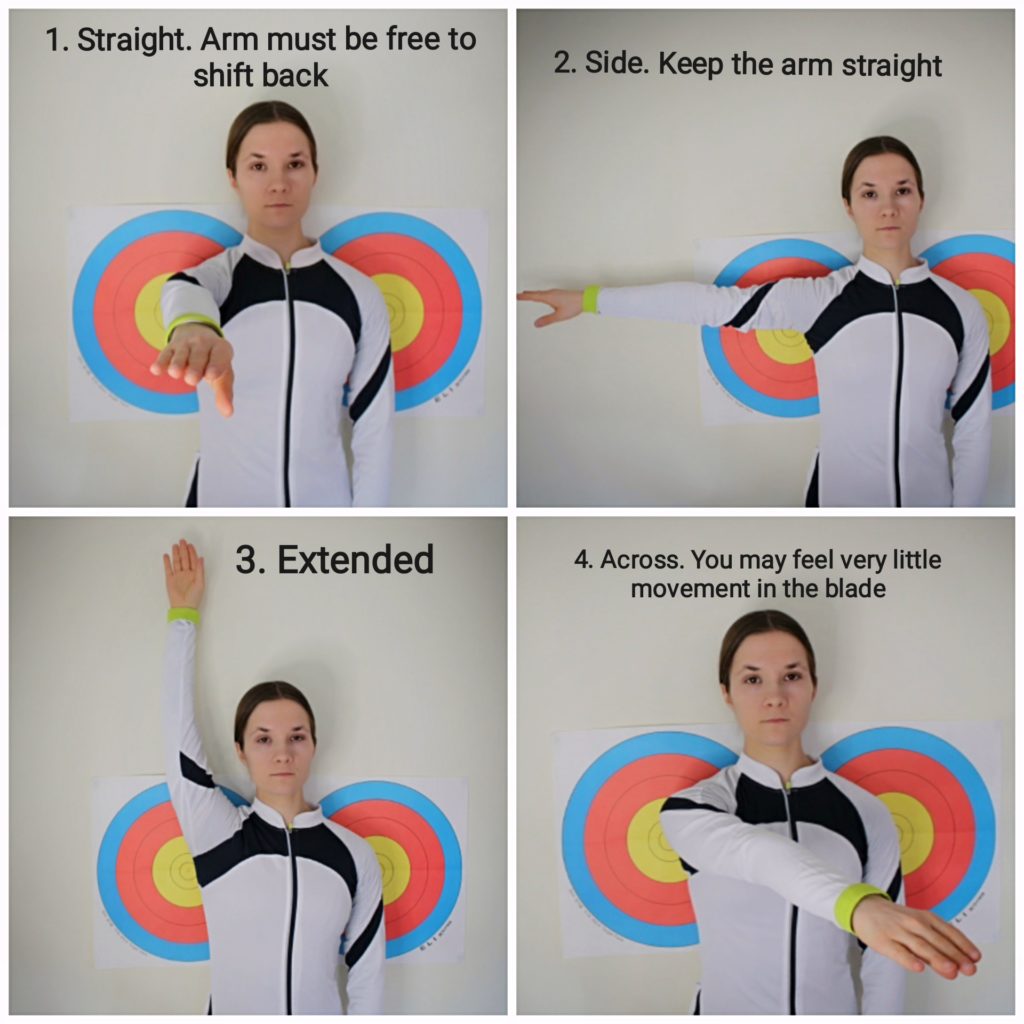

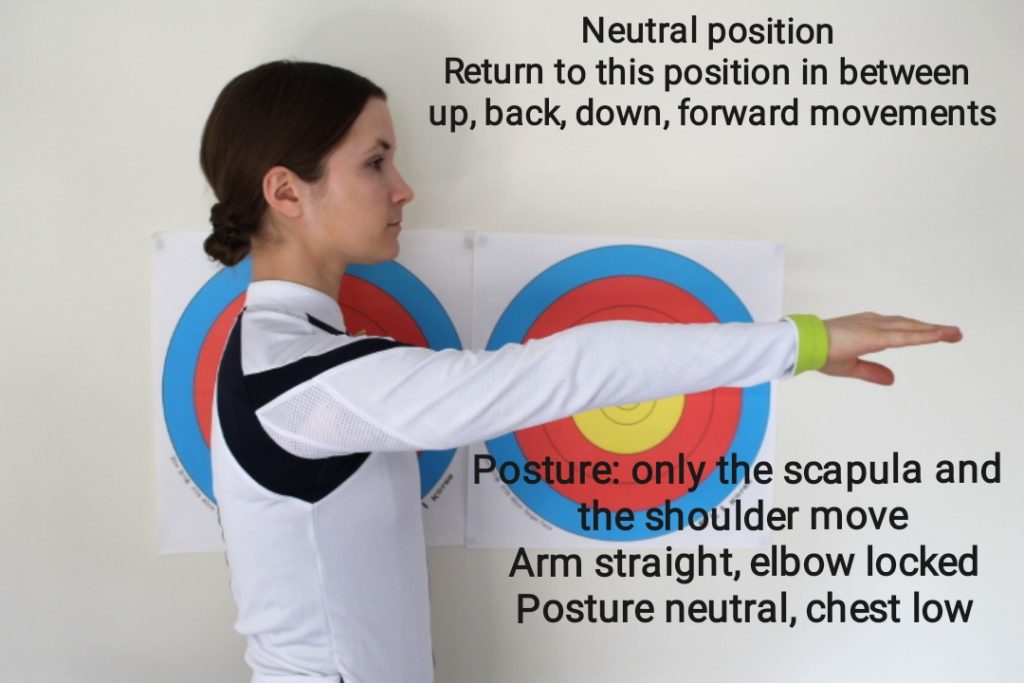

STEP 1 Study four different starting positions for the mobility routine (picture one).

Select position one (straight arm), neutral position (picture two).

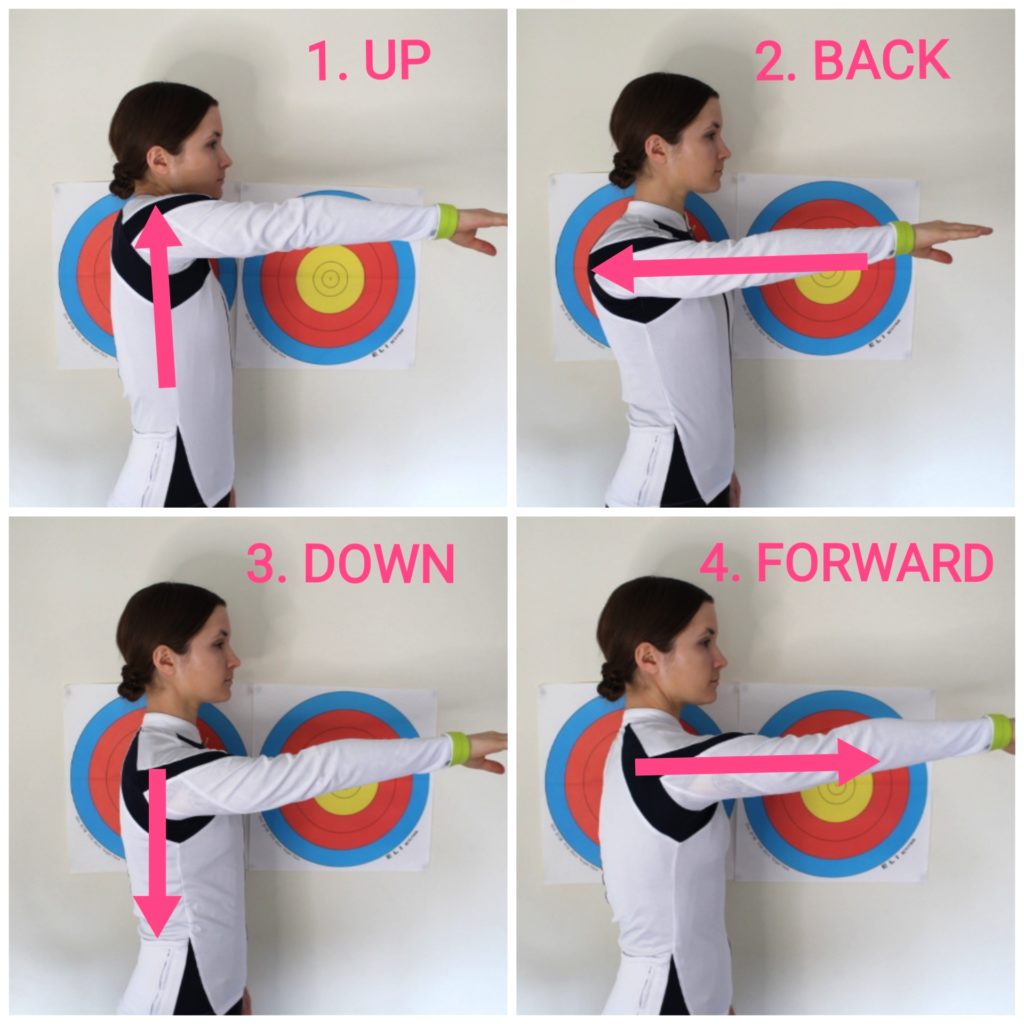

STEP 2 Study the movement sequence (picture three).

Each movement (up, back, down, forward) is performed separately to find individual ROM (for example, up-neutral, back-neutral, down-neutral and so on).

Join all four – shoulder and blade move in a circular motion (like an old locomotive train mechanism).

STEP 3 Master position one (both directions), move on to position two, then three and four.

STEP 4 Take your time and perform clockwise and anticlockwise, on both arms (10 repetitions).

STEP 5 Add a stretch band for resistance, strength and stability training.

‘Motion is Lotion’

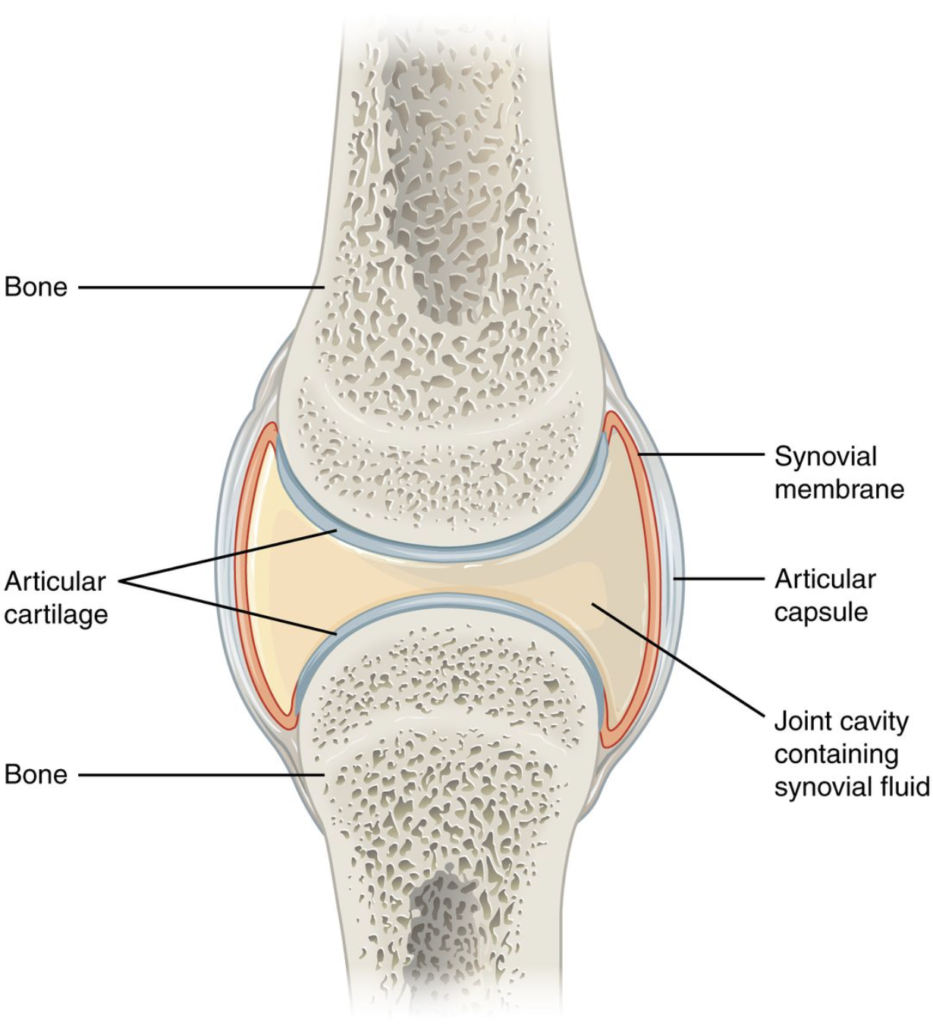

Joint structures are complex. Their key function is to bear weight and move our bodies through space. Every joint capsule (synovium) is cushioned by cartilage, which serves as a protective layer between bony surfaces.

Found in all cartilage is the synovial fluid that lubricates the joint and facilitates the smoothness of joint articulation, reducing friction during movement. It is an ultrafiltrate of blood plasma, partially consisting of hyaluronic acid. The cartilage receives a healthy dose of oxygen and other important nourishing microelements during articulation via the synovial membrane, which acts as a ‘sieve’.

The synovial fluid plays an important role in our daily functioning and sporting pursuits. In healthy individuals, this joint fluid is clear and stringy; in abnormal, it is cloudy and thick. It has been found that when the joint is at rest, the cartilage absorbs some of the fluid.

The body produces more of this important ‘lotion’ during exercise, further emphasising the importance of regular movement and the need for dynamic warm-ups in sports. It is important to recognise the limitations that lifestyle-related (long-term immobility by choice, sedentary lifestyle) or health conditions (such as osteoarthritis) have on the levels of synovial fluid, compromising both mobility (and flexibility as a result) and quality of life. There are special therapeutic interventions and injections (for example, hyaluronic acid shots) that can alleviate pain and boost fluid levels in special conditions.

Pic courtesy: https://www.leeclarkeosteopath.co.uk/

For healthy populations, physiotherapists recommend regular exercise to boost and maintain synovial fluid in those all-important joints – this includes full-body stretching, strength training, and complex and isolated exercises such as quadricep squats, knee flexion and heel raises – and advise against high-fat diets, as these have been shown to increase the inflammation of the synovial fluid, which can lead to many unwanted infections.

It must be appreciated that mobility training must be tailored in developing athletes, because it soon reaches a point past its utility. It must also be accompanied by suitable flexibility training and strength training to achieve the desired technique and stability.

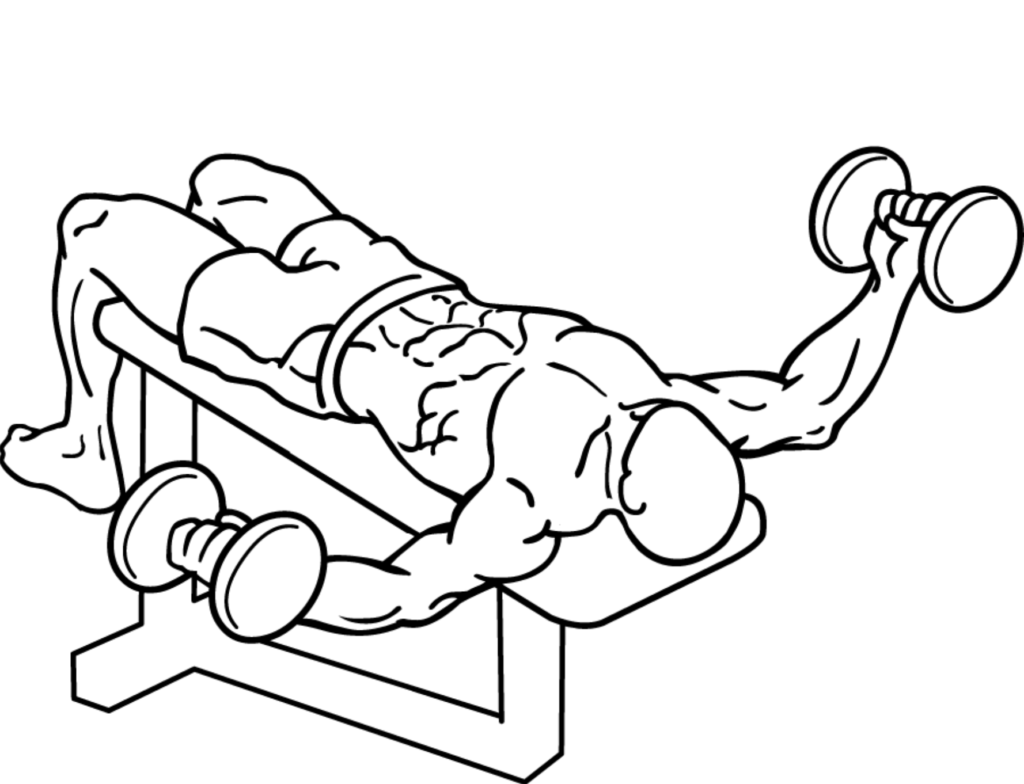

Many warm-up mobility drills will be based on the concept of progressions – in other words, dynamic exercise without implements (empty hand; articulation), addition of the resistance band and, lastly, adding weights or one’s body weight. It is a great way to design your sports warm-up, because here you start with mobility and flexibility, progressing into resistance, strength and weight training. Ever wondered why Korean archers base their junior training and general warm-ups like that? Yes, it is science.

But aside from training based on those principles, and teaching it to my students, I feel it is a smart approach to physical self-assessment; it gives a chance to notice how we feel throughout our ROM that day and what changes we experience as the intensity and loads grow. It is an effective way to diagnose an onset injury without making things worse. Will you be skipping your warm-ups from now on?

In summary, both mobility and flexibility are key factors for optimal function of the kinetic chain (human movement) and are inter-dependent. It is every athlete’s goal to have the ability to move freely and effectively through their optimal ROM.

Demands of the Sport: Archery

A professional athlete, engaged in the sports full time, will have the following differential training needs: flexibility, mobility, strength, power, speed, agility and aerobic endurance. Sport-specific differentials vary from sport to sport; for example, an endurance runner might require more strength and aerobic training to build or maintain stamina, whereas a sprint runner might require more anaerobic loads and engage in more power, speed and agility training.

However, both of those athletes will require mobility and flexibility in their programmes for same or different reasons. It is important to keep in mind that training needs, priorities and their loads will shift in response to the demand of the sport, the training phase, individual ability and medical history.

Archery is best described as a low-intensity endurance sport and is a closed kinetic chain (CKC) sport, in other words, the extremities (legs) are in constant contact with the ground. In closed-chain exercises, the power travels through the body into the immovable object (a bow, a ball and so on), and because the extremities furthest from the body (legs) are fixed, other joints will require motion.

As a result, both proximal (nearest) and distal (furthest) parts involved in the exercise will receive resistance training (strength) at the same time, promoting joint stability and a simulation for functional movement patterns (neurophysiology; nerve ending to muscle connection). CKC exercises stimulate the proprioceptive system by feedback to initiate and control muscle activation pattern, key in learning, development and performance.

An open kinetic chain (OKC), on the other hand, is where an extremity is free or not fixed, focusing on the improvement of strength and ROM of one joint. The biggest benefit for the OKC is the ability to isolate or target a specific muscle or a joint, crucial in rehabilitation and specialist conditioning exercises.

CKC exercises are generally considered as superior due to the nature of co-contraction of muscle groups and the reliance on big antagonist muscles (lower-risk injury potential). However, joint mobility may be compromised, depending on the forces, repetition and loads in the programme.

Bottom-up Mobility Warm-Up

This is a varied routine that will massively increase your mobility. Some of these exercises may well be unfamiliar and it would be an entire article to explain them all. The best way is to look them up on YouTube – go for physiotherapy channels.

For each exercise, aim at the start for 10 repetitions each side of the body and gradually build.

Ankles: ankle dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, circles

Hips: circles (both directions), walking hip openers, hip abduction, hip adduction, hamstring stretch

Trunk: thoracic spine windmill floor – with the foam roller thoracic spine windmill wall – at the wall, standing supine leg cross, standing cross-legged side stretch, yoga warrior pose trunk rotation variations

Arm, Shoulders, chest: Arm circles – small, medium, large, both directions, shoulder pass-through – stick, PVC pipe, strap or belt

Neck: circles, side/back/front stretches, chin circles, all directions

Finisher: jumping jacks (many variations to challenge your coordination and balance as a bonus, plus cardio)

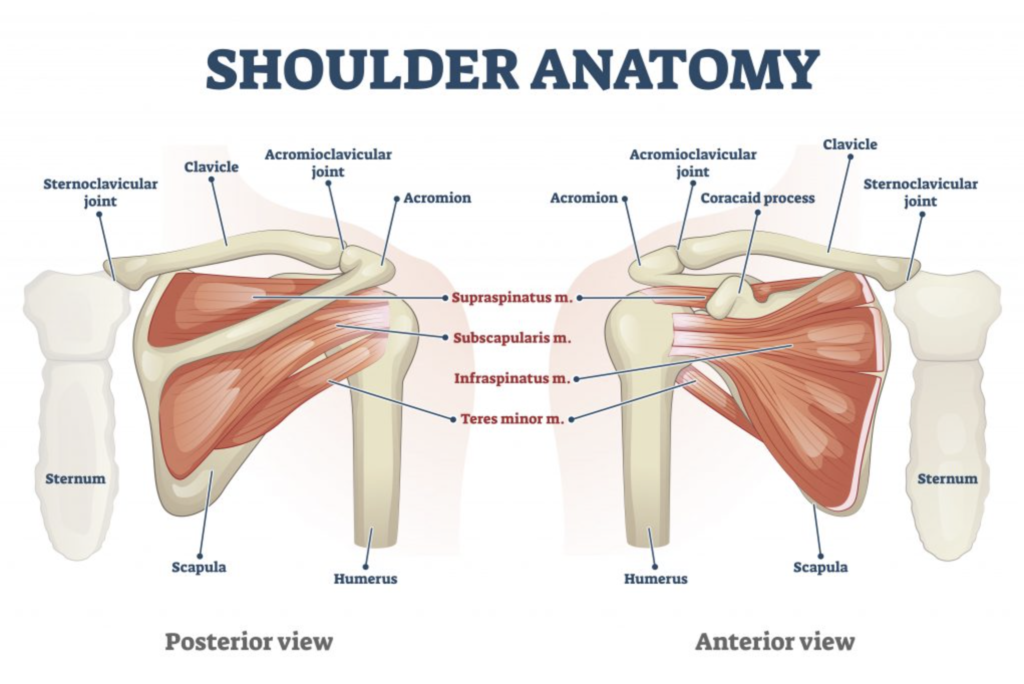

Archery and Shoulders

Out of all overhead sports, archery is reported to have the highest frequency of shoulder injury. All overhead sports demand a delicate balance of shoulder mobility and stability, but the prevalence of shoulder injury in archery is likely to be explained by the technical (technique) demands of the sport. For archery, the processes of skill acquisition, its automation and performance, rely heavily on repetitive motion.

The sports injury and illness incidence report from Rio Summer Olympics of 2016 examined a 17-day period. The reported occurrence in the total of 11,274 athletes across all disciplines (5,089 women, 45%; 6,185 men, 55%) was that 8% of athletes incurred at least one injury and 5% at least one illness. The highest injury incidences were reported in BMX cycling (38%), boxing (30%) and taekwondo (24%), while archery, shooting, golf, rowing and table tennis reported 0% to

3% of the total.

Though there are no accurate statistics for the nature, severity or frequency of occurrence of injuries in sports, the existing meta-analyses show that sports such as boxing demonstrate a low injury count in practice and a high one in competition. Archery exhibits the opposite – most injuries occur during training.

The nature of the prevalence of reported injury types indicates the direction in which the training should be skewed. Most archers suffer from musculoskeletal injuries, particularly to the shoulder, neck or back areas. The prevalence of soft-tissue damage is not surprising, given the repetitive nature of the sport. Archers must pay particular attention to bilateral training (both sides) to help balance out the asymmetry that occurs because of the long-term implementation of archery form.

Because it is a CKC sport, it is vital to include all the joints in mobility training. You can take the bottom-up approach (ankle, knee, hip, trunk and so on) to your mobility routine, focusing on full articulation of those in order, moving in circular, rotational, twisting motions in both directions.

Before embarking on any mobility training, it is a good idea to record individual joint ROM, so that you can observe changes over time and adjust your training accordingly. Your local physiotherapist or NHS provider should have those in open access or upon request, but better yet, arrange to be observed by the professionals.

Correct/optimal technique, better bow poundage management, training periodisation (tapering and peaking of performance), appropriate warm-up and cooldown protocols are paramount in archers’ training and must be tailored to the individual.

Archery does not compare with the more popular sports and does not have a strong academy standard approach like football or rugby. Archery is a diverse sport, but it comes with many challenges for developers and coaches. The athletic pool consists of a much more diverse group of individual physiologies and histories.

Final Note

Mobility and flexibility training are the foundation for movement and are key to development of strength, speed, agility, power and endurance. Every athlete has the right to enjoy their developmental journey, gain confidence and competence – a long-term process. An adequate and well-informed coach is key to the task of providing a balanced sporting life for their students.

Continued coach education on the physical, technical and mental aspects of the sport should be at the top of the agenda for sports’ governing bodies, because coaches are the people who spend the most time with their athletes. Coaches are in the best position to introduce, implement, observe and amend the training programmes as well as monitor their impact on athletic performance beyond numbers and scores.

Disclaimer

Each person’s physical development path is individual. Seek professional consultation to address your individual needs to avoid injury and achieve effective performance. Visit your local sports physiotherapist, strength and conditioning specialist, a coach and other relevant specialists in the field.

This article uses scientific, evidence-based academic material to introduce and contextualise mobility training in sports and provides some basic guidance you can apply to your archery training.

Should you have any queries regarding any of the statements or suggestions made in this piece, you can contact Kristina at thirdeyearchery.com