Continuing on in a history of arrows, Jan H Sachers takes us from the rise of the knights to the sinking of the Mary Rose

With the advent of the knight in the 11th century, the social elite fought with lance, shield, and sword as a mounted warrior in armour, while the cheaper bow was a weapon of the lower ranks of society.

Literature of the era, however, paid little to no attention to the common infantrymen, and they are rarely depicted in contemporary illustrations, which led to the impression they had been absent from the battlefields.

In open battle, the bow’s quicker shooting rate still made it superior to the much-more expensive crossbows that took their time to be spanned, and hence archers are likely to have remained a part of most regular armies from the 12th to the 16th centuries, even if they relatively left little trace in recorded history.

In the crusading armies archers certainly played a crucial role, even if they were often paid mercenaries from Armenia, Syria, and other local regions.

An important pictorial source from the 13th century, the so-called Maciejowski or Crusader Bible, shows an archer with a very particular bow in defense of a town or castle, which may be considered one of the main tasks for professional archers.

General observations on arrows

Most high medieval illustrations of arrows show bulbous nocks and triangular or parabolic fletching secured with a thread whipping. The arrows under the belt of philosopher and author John Gower (ca. 1400) may have glued on nocks of horn or other dark material.

Arrowheads are commonly of the wide two-bladed and (often) barbed variety, which is easy to recognise, and depict in paint.

The martyrdom of St. Sebastian became a popular subject for artists in the late Middle Ages. A famous example from the 15th century (Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne) shows archers with strong yew bows.

Their arrows are made with adequately thick shafts, perhaps tapering towards the nocks, long triangular fletching, and swept-out ‘swallowtail’ heads with two curved blades.

This painting is likely to give a good impression of real arrows from that time. The depicted arrowheads would have been of good use in both hunting and warfare against unarmoured opponents.

In a portrait of Anton, ’the Bastard of Burgundy’ (Rogier van der Weyden, ca. 1460) he is holding an arrow in his hand which has a shaft clearly tapering towards the bulbuous nock.

It is fletched with three white feathers of parabolic shape without whipping. The cock-feather is marked by two thin red stripes.

Hunting arrows

Bows and arrows were a favourite hunting weapon for both nobles and common folk – even though the hunting practices of the latter were usually classed as poaching and are mainly documented in court protocols and other judicial documents.

The noble hunt on the other hand increasingly became the subject of illustrated manuscripts from the 14th century onwards. Here we find arrows not only in image, but also in descriptive texts, which finally offer some details on their manufacture and use.

Gaston Phoebus (1331-1391), the Count of Foix and most famous hunting author of the late Middle Ages recommends two-bladed arrowheads, ‘well sharpened and filed’, which should be ‘five fingers long and exactly four fingers wide’ between the barbs. The arrows depicted in his ‘The Book of the Hunt’ match this description quite well.

Wide, two-bladed arrowheads were able to make big wounds causing heavy blood loss, so the prey was weakened quickly if the hit had not been fatal at once.

Another kind of arrow is often shown in hunting treatises and other book illustrations as well. It has a blunt wooden tip and is used for hunting hare, rabbit, squirrel, and other small furry game, so as not to damage their pelt.

The late medieval illustrated examples appear bigger than the originals discovered in Haithabu, which may be due to artistic license or reflect an actual change in design.

Petrus de Crescentiis, a 14th century author, recommends the use of a special arrow to hunt big birds. The ‘sagitta bifurcata’ was a forked point with two blades sharpened on the inside.

According to Petrus it was able to cut through a wild goose’s or other large fowl’s neck or wing. Examples of such arrowheads have indeed been found, but are mostly referred to as ‘rope cutters’ in modern literature.

English archery

The situation in England differed from the rest of the continent. After the experiences of the Welsh and Scottish wars, contingents of archers remained a regular part of practically every English army until well into the 16th century.

Archery became a mandatory exercise for all able-bodied men, and the yeomen archers who could handle the strong yew warbow were held in much higher esteem – and paid considerably more – than in other European countries.

Documentation of production, storage, and use of arrows is particularly rich for the time of the Hundred Years War (1337-1456) with France. For example, it is recorded that in the year 1360 alone, half a million arrows were delivered to the royal armouries in the Tower of London; the year before it had been another 850,000.

Fletchers throughout the country were responsible for this mass production, but they supplied not only the Tower, but also other royal armouries as in Bristol (11,000 arrows in 1346) as well as individual nobles who had to equip their own personal retinue.

Raw materials were also stored centrally. In 1417 six feathers from every goose within the realm had to be delivered to the Tower, with the Counties being mandated to supply a total of 1,190,000 goose feathers in the following year.

In 1417 six feathers from every goose within the realm had to be delivered to the Tower of London

To secure the supply of good wood for arrow shafts, King Henry V banned the use of poplar for any other use in 1416, particularly the manufacture of wooden shoes.

Surviving original arrowheads show a few interesting details. While many arrowheads classified as hunting points show a small hole where the socket was fixed to the shaft with a small nail or rivet, this is absent on arrowheads for warfare.

Most likely these were just pressed onto the shaft or loosely fixed with beeswax, which was not only more economical, but had several advantages. When pulling the shaft from a wound, the point was likely to remain inside. Shafts without heads could not be re-used by the enemy, while arrowheads could easily be removed from broken shafts and re-fitted.

The fletcher’s trade

Bowyers and fletchers in London originally formed a common guild, until the latter petitioned for a strict separation of the crafts in 1371, and The Worshipful Company of Fletchers was founded.

In other European countries fletchers never seemed to have formed their own guilds. In Germany they were mainly found in the bigger towns, their products sold by traveling merchants in times of peace. They only supplied the shafts with fletchings and nocks, while the customer had it equipped with forged arrowheads.

Customers included noblemen, wealthy citizens, and the towns themselves. The latter in particular bought large quantities, but since European fletchers produced not only arrows, but also crossbow bolts, and the records do not distinguish between the two, it is impossible to quantify the use of bows and arrows by these numbers alone.

Being of strategical importance for war and also the defense of towns, fletchers often profited from tax reduction or even exemption as in 14th century Vienna.

Arrow shafts from the high and late Middle Ages were made from wooden boards. A special jig was used to turn staves of square cross section into rounded shafts with a selection of planes. Sandstone and fish skin smoothened the surface, the nock slit was cut into the wood with a small saw.

It is not clear when the reinforcement of the nocks with a sliver of horn became common. 14th and 15th century illustrations often still show the bulbous nocks instead, which had been in use for centuries, particularly with tapered shafts.

The fletchings were mainly attached using skin glue, sometimes mixed with beeswax, verdigris (copper sulphate), and other components to keep insects away during long times of storage.

The fletchings were additionally secured with a whipping of silk or linen thread, since skin glue is not water resistant. Judging by the illustrations, popular shapes of fletchings included parallelogram, triangular, parabolic, and ‘banana’.

Of all indigenous birds, only goose and swan produced feathers long and strong enough to be used as fletchings, and available in large enough quantities – the turkey only being introduced to Europe from America much later.

Feathers from birds of prey such as eagles as well as from pheasants and peacocks were probably used for individual hunting arrows, but not suitable for mass production.

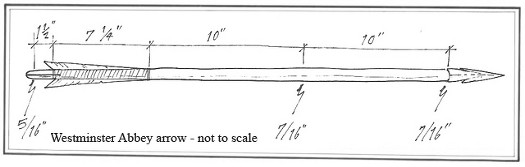

To this day, the only complete late medieval arrow was found in the rafters of the capital house in Westminster Abbey, where it must have been placed before the renovation in 1437.

The shaft is 29 inches long, probably made of ash, with a diameter of 10.7 mm beneath the socket and 7.6 mm at the rear end. The widest part of 11.4 mm is at about two-fifths of the total length behind the arrowhead, a shaft design known as ‘breasted’ or ‘chested’.

A 4 cm long slit was cut perpendicular to the string groove at the rear end, probably to receive a thin sliver of horn as reinforcement.

Reddish-brown remains of a glue covered some 18 cm (7 in.) of the rear end in which three feathers and an increasingly narrow binding have left their marks.

The heavily corroded head was a type very popular in late medieval England with narrow, curved blades and barbs.

Arrows from the Mary Rose

The sinking of Henry VIII’s flagship Mary Rose in the Solent near Portsmouth in 1545 proved to be a treasure chest for archaeologists. It carried, among other things, 172 yew longbows and several thousand arrows, 2,900 of which have been recovered and analysed.

Most of them were bundled in sheaves of 24; up to 40 of these bundles fit into special wooden boxes, some of which were also salvaged.

Lengths of these arrows vary, but the vast majority (841 of a total of 1,054) measures 31 inches, with the longest being 32.5, the shortest 27.5 inches long. (Essentially, arrows were standardised ammunition, even if bow weights varied with the archer.)

Their front ends are tapered conically, with a marked shoulder to receive the arrowhead socket. The average diameter at the shoulder is ½ inch, tapering to ⅜ inches towards the nock. Narrow slits two inches long sometimes still contained remains of the horn reinforcements.

(Photo by Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images)

More than three quarters of all analysed shafts are made of poplar, others of ash, birch, and even oak as well as at least six as yet unidentified types of wood. Most of them taper evenly towards the nock, considerably fewer are parallel, barrelled, or chested.

Glue remains indicate an average fletching length of six inches; feathers were aligned radially and secured with a thread whipping. Unfortunately, the iron arrowheads have been destroyed by centuries in salt water.

At least those arrows bundled in leather discs – probably as part of a linen arrow sack – were probably equipped with narrow type 16 or bodkin type points.

In the same year the Mary Rose sank, Roger Ascham published his treatise ‘Toxophilus. Or, the Schole of Shooting’, the oldest known archery manual in Europe. His work is dedicated to target archery, which differs in great many respects from what was common or required in hunting or war.

Ascham recommends shafts of ash only for war arrows, since it is heavier and at the same time faster than the more popular Aspen. Apart from other well-known types of wood like birch and oak he also lists exotic materials such as Brazil wood, turkwood, fustic, or sugar maple.

He also mentions footings, and splicing in hardwoods at the nock to counterbalance heavy arrowheads – practices that were far too lavish for mass-produced war arrows.

‘Toxophilus’ is evidence for a transformation of archery in England during the 16th century, when the bow was more and more replaced by firearms as a weapon of war, and turned into a piece of sporting equipment.

Recreational archery required lower draw weights, different types of arrowheads, and many other changes in gear and shooting styles. With the sinking of the Mary Rose and the drowning of many of the king’s own archers, and the publication of a civilian archery manual the year 1545 may be considered a pivot point in the history of English archery.

However, unlike in most other European countries, archery remained a part of the English tradition and heritage, and even its medieval forms are making a comeback – with much reproduction equipment still available today.

If you are going to use my drawing of the Westminster Abbey Arrow please credit the drawing to http://www.warbowWales.com

Hi Jeremy. Can you email the editor on john.stanley@futurenet.com

Thanks.

This is so HELPFUL! I had to do a research paper, and I LOVE IT! Can you send me emails whenever a new article is released?

This was very educational. Thank you.

There is a second medieval arrow in existence owned by myself and Richard Head. It, like the Westminster arrow, has not been scientifically dated but has been verified by some of the top bowyers and fletchers in the country.

Toxophilus is not the oldest treatise on archery in Europe.

This French manuscript is from 1515.

https://www.archerylibrary.com/books/gallice/

as a beginning ‘long bow’ re-enactor I’m very happy with this knowledge. It means I’m well equipped for my time-period (1470).

Thank you.

I’m not sure if your membership is aware of the publication “L’art de Archerie published in 1515 which makes it the earliest archery publication discovered so far. It discusses arrows of the period in some depth and read in conjunction with the Tower inventories makes compelling reading. here is the link…. https://www.archerylibrary.com/books/gallice/

Since the Mary Rose arrow discovery the Tower of London Inventories from the mid 1300’s have been translated in 2012 from Latin, Anglo Norman and middle English and give a comprehensive view of bow and arrow manufacture, purchase and distribution which now cast doubt on the purpose of the Mary Rose arrows.

There were only two categories of arrow, the yard long war arrow and everything else. Everything else was all commercial arrows for hunting, target and flight shooting. Almost all, both commercial and military, were made of aspen (Poplar Tremulus). The flights of commercial arrows were whipped (also known as waxed) and in most cases the heads were pinned, bound or heat shrunk on so the arrow could be removed intact from target or prey, these arrows were made to be reusable and could last many years whereas the military arrowheads were push fit so as to come apart when trying to remove from shields or flesh and unwhipped as they were considered a single use missile.

The Mary Rose arrows show signs of bound and glued heads judging from two inch stains up the shaft with whipped flights. This makes them expensive re-useable arrows, not to be fired over water never to be seen again. It is understandable that when the the ship was cleared for action they were left deep in the hold as cargo. The bows may have been ships bows judging by draw weight. Although the Inventories for the 1500’s are not published it highly unlikely these arrows were commissioned by the Tower/Crown.

Clue……the barrel shown in the 14th century painting is a pipe (126 gallons) and stands around 37.5 to 41 inches high. It is half a TUN (256 gallons)