Rob Jones finds out who is still carving a path

There are thousands of archers in the UK, shooting at local clubs or competitions the length and breadth of the country. Many will be shooting the latest bows from Hoyt, Mathews or another overseas manufacturer. A few might be shooting more traditional bows, but not all are aware of the home-grown talents of the UK bowyers, large and small.

In this article I’m going to chat with a few – exploring why they started, where it’s taken them, how they learnt their skills and what’s possible for those who wish to progress further. For some, it’s a part-time business or a very serious hobby, seeing them produce a dozen or so custom-made bows a year. For a few, it’s a full-time business; for a handful, it might be a lifetime career path.

A shared passion

Many of these individuals have been in the business for decades, others for only a few years. But all of the ones I’ve spoken to share one characteristic: a strong passion for bowmaking in its many guises, whether this be the history of its development, a desire to keep old skills and knowledge alive or a drive to push the boundaries of what’s possible by introducing new designs and materials.

For Rod Harris of Team Sagittarius (teamsagittarius.com), it’s the romance of the sport that hooked him at an early age, with his interest being sparked by watching bows being made at the age of nine.

This stayed with him, and in 2014, he made the decision to build a dedicated workshop, starting to commercially produce his bows the following year. He now ships his bows and other archery items worldwide.

Like many bowyers, he started with making English longbows before moving on to build his own formers and developing these through a process of trial and error. Rod is especially passionate about Howard Hill-style flatbows, and his attention to detail in all stages of construction is not surprising when you realise he’s a carpenter by trade and will only work on one bow at a time. “It’s the tillering of the bows, where the real science and skill comes in,” Rod explains.

He freely admits that for a novice, it can feel like a minefield when trying to learn, especially when it comes to seeking advice. Unlike modern Olympic recurves, which allow you to tune and make micro-adjustments to nearly all aspects of the bow set-up, traditional bows have considerably fewer tuning options, so it’s even more crucial that they are constructed right from the outset.

The English Longbow

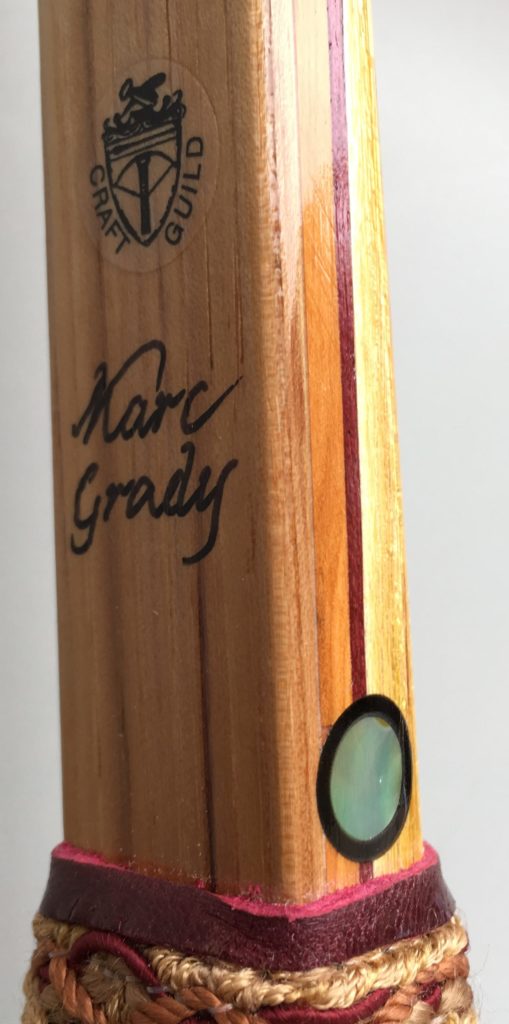

Often when we talk of UK bowyers, the image that comes to mind is of the makers of the classic English longbow, it being seen as the quintessential weapon of Albion. Two legendary exponents of this art are Marc Grady of the Longbow Emporium (longbowemporium.co.uk) and Pip Bickerstaffe of Bickerstaffe Bows (bickerstaffebows.co.uk).

Pip has well over 25 years in the industry and has seen many changes, including formations of some of the national societies, such as the National Field Archery Society. But it wasn’t until the 1990s that he made the decision to go full-time as a bowmaker. Since then there has been slow and steady growth, and some 20,000 bows later, he still tillers every bow that leaves his workshop.

Bickerstaffe’s standing is even more impressive when you hear him describe himself as a “self-taught bowyer”, having learned most by studying as much as he could from the bowyers of the past – reading all of the old archery books he could find while studying the designs and styles of all kinds of bows from all over the planet.

Essentially, he taught himself how to make bows by making bows, developing a step-by-step process, learning from the previous one so the next one is improved, and onwards. At one point, he had the opportunity of handling the Mary Rose bows, which he described as “educational”.Describing his bowmaking journey, he says: “There was a steep learning curve. But experience is the best teacher. You stand or fall by what you do.”

Pip makes absolutely clear the importance of learning every stage of the process and steps from planning, to gluing up, to finishing, along with how to select and grade wood. Key skills include making sure that all of the glue lines are sound and that the gluing techniques were as good as possible, using the correct glues to work with the woods. His aim for his bows is good speed, consistency and longevity.

The selection of the correct grade and quality of wood is one of the struggles many are now facing, with it becoming increasingly difficult and costly to source some materials. This can be a factor that puts off those interested in starting their bowmaking journey, as it increases the fear of failure.

Family ties

While some are new to the craft, others have spent decades developing their skills. Still others have followed in their family footsteps.

Marc Grady of the Longbow Emporium is one of those. Qualifying as a Master Bowyer in 2014 following a three-year apprenticeship, he describes himself as a “dyed-in-the-wool traditionalist” archer of the “green and white”. It’s less surprising that he chose this path when you find out his father was a Master Bowyer.

Since then he’s been making bespoke bows for clout, field, target and re-enactment. I asked what his goals were. “I pride myself in not just making fast, reliable and sweet-to-draw bows but also bows of great beauty,” he tells me. “I have spent most of my bowmaking creating fast, flat-trajectory target bows.”

He makes bespoke bows to the customer’s physiology and needs alongside the style of shooting they want to engage with.

There is a huge history of bowmaking in the British Isles, and Marc took the time to explain how there are craft guilds in the UK that were specifically set up to keep the skills and knowledge alive – skills that might otherwise be lost.

He has a real passion for the history of bowmaking through the ages along with a historical understanding of bowmaking and longbow shooting. Marc is well placed to explain the role of these guilds as the current warden to the Craft Guild of Traditional Bowyers & Fletchers as well as chairman of the Royal Toxophilite Society, chairman of Archery England and freeman of the Worshipful Company of Bowyers in London. To become a Master Bowyer in the Craft Guild, there is a three-year apprenticeship, and this remains the only formal qualification in longbow making in the world.

Custom composites

Not all bowmakers are focused on the traditional styles. Some, such as Roger Massey, are wanting to combine exotic woods and carbon fibre to create custom composite bows. Roger runs 1066 Field Archery (1066fieldarchery.co.uk) and considers himself a newcomer to the field of bowmaking, but he has embraced it with a passion.

He describes it as “a serious hobby” that sees him spend hours on research, design and development of new bow formers. Even as a hobby, it sees him spend 30 to 40 hours of work per bow. While it’s not a full-time job, he says: “I get loads of enjoyment from shooting my own bows and seeing others enjoy shooting them.”

Roger loves playing around with designs – doing a bit of research and development (R&D), as he calls it – which sees him exploring new materials. This drove his decision to buy some bow forms and design information from Andy Soars, who owned Blackbrook Bows, prior to Andy’s retirement.

He explains how this really helped him develop as a bowyer. “There are some things you just have to learn by trying yourself and other things you can learn from others who have already trodden the path you are thinking of walking.”

Roger embraces the R&D side of applying new materials and bow formers for his composite wood and carbon-fibre bows. His desire is to combine a traditional-style bow with speed and a flatter trajectory.

Learning the art

It strikes me that the ways these bowyers learnt their trade are as diverse as the bows they make. There is little doubt that learning the skills is a long process, taking many hours over the years in workshops. It can be a painful process of trial and error as no two pieces of wood are identical. Some craftsmen are self-taught, while others have gone down the apprenticeship route to learn their skills.

For the future, unlike in previous generations, enthusiasts can call on the power of the internet, with YouTube alone hosting hundreds of hours of ‘how to’ videos on longbow making. The problem is that not all ‘how to’ guides are created equal.

Both Rod and Roger mentioned how Facebook groups can be useful for asking for help or advice, though social media can also be a bit of a minefield for newcomers as everyone is willing to share their perspective of what is the right way of doing something. There are now numerous Facebook groups for bowyers to pose questions, part of the wider, Facebook-connected international archery networks that are enabling connections – and businesses – to flourish like never before.

There is a wealth of knowledge, expertise and passion in the UK bowmaking community, members of which all share a passion not just for the sport but the craft that has taken many hundreds of years to develop into what we see and enjoy today.

Roger ,

I’ve been looking for some pictures of your bows and can’t seem to find any. I’m interested in a 66″longbow fro 3D tournaments here in USA.

Can you point me in the right direction to see what you have avail or custom make.

Best regards,

Ray Iglesias

Good evening. We are forestry company and have come into possession of many full lengths of Yew. They range from 8 inch wide to 1 meter wide and all 3 meters long. would this be something you may be interested in purchasing ?