The finds that changed history. By Jan H Sachers, MA

Even today’s archaeology, with its sophisticated modern technology, cannot answer the question: when was the bow first invented? It is, however, an established fact that the arrow pre-dated the bow by several thousand years, in the form of long, thin, fletched spears cast with the help of a spear-thrower, or atlatl by its Aztec name.

The oldest known ‘arrow heads’, with wildly varied dating, are most likely to be the sole remains of these widespread and surprisingly efficient weapons. Only shaft remains with a nock slit to accommodate a string could by inference prove the actual existence and use of bows, but since they were made of wood, none older than approximately 10,000 BC have thus far been discovered.

It seems likely that the bow was invented in northern Europe sometime between 20,000 BC and 10,000 BC, and independently in other regions at some similar, or other, point in time. However, the oldest known examples of bows, or fragments that could with absolute certainty be classified as parts of bows, date from the Mesolithic Age and were found in surprisingly large numbers all over today’s Denmark and other parts of northern Europe.

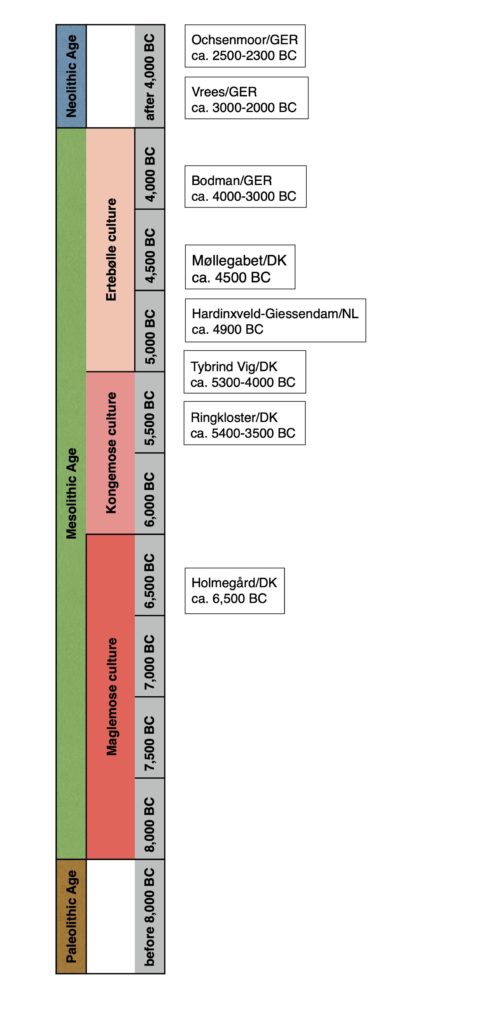

The Mesolithic Age in Northern Europe

In the region in question, the Mesolithic Age lasted from approximately 8,000 BC until circa 4,200 BC. Typical remains from that period are small arrowheads made of flint called microliths, and hafted axes with flint heads. Generally, however, archaeological finds from the Mesolithic Age are not too numerous, not only because tools and equipment were made from perishable materials, but also because they were lost or destroyed when the later Neolithic cultures developed agriculture and dug up the ground for that purpose.

In Denmark, three distinct Mesolithic cultures succeeded one another. Because of their preferred locations for settlement, they are also known as the Danish coastal cultures. The earliest (circa 8,000 BC to 6,000 BC) is called the Maglemose culture, after the Maglemose moor on the west coast of Zealand, and was also native to England, northern Germany, southern Sweden and the Baltic coast. Typical finds are microlithic blades and arrowheads, bone spearheads and different types of flint axe heads. The Maglemose people also left the oldest known paddles, curved fishing hooks, and drills, and they experimented with pottery.

Around 6,000 BC, the coastlines of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea altered. The mean summer temperature rose to 20°C, the last ice caps melted, sea levels rose and the climatic change led to changes in fauna and flora as well. The primeval forests grew dense with oak, alder, ash, linden and elm. Denmark was inhabited by animals that have since died out or moved to more southerly regions in Europe.

The Kongemose culture (circa 6,000 BC to circa 5,200 BC) built coastal settlements and used traps and nets for fishing and big and heavy flint arrowheads of rhombic shape for hunting. Decorated daggers of bone with inserted flint blades have been found frequently. The Kongemose people also inhabited Denmark as well as England, southern parts of Scandinavia and the coastal regions of middle and eastern Europe.

They were succeeded by the Ertebølle culture, the last of the Mesolithic cultures in northern Europe (circa 5,200 BC to circa 4,100 BC). Remains of settlements have been found in coastal regions, some of them now submerged, but also inland, for example Ringkloster, Muldbjerg I (Zealand) or Ellerbek in Schleswig-Holstein (northern Germany). Archaeological finds include fishing hooks, spears, nets, fish traps, remains of boats and paddles and, most characteristically, transverse or chisel-shaped arrowheads, also known as tranchet points.

Mesolithic bows

A considerable number of bows or fragments dating from the Mesolithic Age have been discovered at different sites in Denmark and northern Europe. They usually survived due to anaerobic conditions in moors, or under water, and show great similarity in general design while differing in detail.

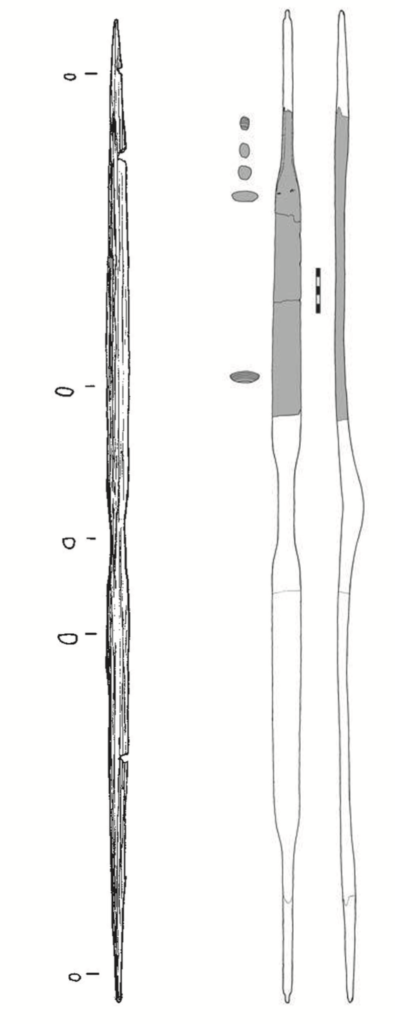

The finds from the Mesolithic site Holmegård IV in Zealand/DK – one complete bow, one fragment – are dated to circa 6,500 BC, making them the oldest bows in the world discovered to date. They were made of elm wood (Ulmus glabra) with very narrow growth rings, indicating the trees had grown in a shady place. Since they are of very distinctive design, later bows of similar shape are referred to as ‘Holmegård type’. Characteristics of this design are:

- A deep and narrow grip section

- Wide and flat limbs

- The widest parts of the limbs are above and below the handle, tapering towards the ends

- Limb cross-section of a flat D shape, with rounded back and flat belly

Roughly one dozen complete bows of this design and a number of similar fragments dating from circa 6,500 BC to 1,700 BC have been found in Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden. Despite their significance, not all of these finds have been documented and published properly and, moreover, dates and measurements given for certain artefacts can differ quite a lot in recent literature, and sometimes it isn’t even clear if a statement refers to one and the same bow or two different ones.

The complete bow from Holmegård measures approximately 152cm in length. The handle section is 2.7cm wide and 2.5cm thick, with a length of around 14cm. Beyond the deep grip, the limbs become flat (1.8cm to 1.9cm) and wide (around 4.4cm), then taper constantly toward the narrow tips.

The limbs show a flat D-shaped profile, the convex side facing outwards. The bow was apparently cut from a small elm trunk approximately 5cm in diameter, its de-barked, naturally convex surface forming the back of the bow. The string was probably attached to small shoulder nocks.

A similar elm bow from Ringkloster, in Jutland, Denmark, measures 154cm, one limb being almost 5cm longer than the other. The widest parts of the limbs above and below the grip measure 3.4cm and 3.1cm respectively, with a thickness between 1.5cm and 1.65cm.

Bows of similar design have been found in Tybrind Vig, Ronaes Skov, Agernaes, Vedbaek, and Muldbjerg (all in Denmark), Hardinxveld-Giessendam and De Zilk (the Netherlands) and Vrees, Forstermoor and Ochsenmoor (all in Germany), all measuring around 115cm to 194cm in length and dated between 6,500 BC and 1,700 BC.

A fragment from Møllegabet in Denmark is dated to circa 5,400 BC and may have been part of a children’s bow, since the complete bow was probably only circa 115cm long. The wide and flat limbs ran parallel for around two-thirds of their length, when they suddenly became narrow and thicker, resulting in stiff, but not inflexible, tips.

Also notable is an example of a Holmegård design bow measuring 150cm in length, with 3.7cm-wide limbs, dated to 4,000 BC-3,000 BC, found in Bodman in southern Germany, around 1,000km south of Denmark. Like the bows from Ochsenmoor and Vrees, it was made not of elm but yew.

The Technology of the Mesolithic bows

Of all European bow woods, elm is inferior only to yew (Taxus baccata), which didn’t spread into these northern parts until the third millennium BC.

One way of mitigating the risk of breakage in a powerful bow is ‘overbuilding’ – making the limbs broader so that the stress is distributed over a wider surface. Since stress is distributed unevenly in a bent bow – more of it close to the middle and lesser towards the ends – the limbs can be made to taper towards the nocks, reducing their mass and therefore increasing cast, a principle that has been applied in a somewhat extreme way in the child’s bow from Møllegabet. Also, with wide limbs there is no need for a rounded, high-stacked belly.

To ascertain a comfortable grip, and to account for the archer’s paradox, the handle section needs to be narrower and deeper than the limbs, making this part of the bow rigid, and thus preventing it from ‘kicking’ in the hand when shot.

Stone tools are less efficient than metal ones, which is beneficial in that they reduce the risk of removing too much material unintentionally. On the other hand, they make bow building a tiring, arduous and time-consuming exercise. Therefore, a bowyer would naturally strive to keep the amount of work applied to a single stave as limited as possible.

This includes using a trunk of comparatively small diameter, and utilising its de-barked, but otherwise untouched, natural surface as the rounded back of the bow-to-be while removing material only from the belly. This method also makes sure the outer growth ring is not damaged, a fact that further reduces the risk of breakage under tensile stress.

Mesolithic bows with growth rings still visible show that this method was the common way of building a wide-limbed flat-bow from straight, knot-free elm trunks of small diameter that had grown slowly in the shade, thus producing a very narrow grain.

The Mesolithic bowyers obviously made use of the best bow wood available to them in the most efficient manner. This probably goes a long way to explain why bows of Holmegård design have been in use for (at least) roughly 5,000 years in an area that seems to cover Denmark, northern Germany and the Netherlands, and perhaps other regions as well. In fact, the Holmegård design and its variations seem to have been so successful that even when yew wood became available in northern Europe, bowyers made use of the new material but kept the ‘traditional’ shape.

The Holmegård-type bow had its heyday from circa 6,500 BC to circa 1,700 BC, when it dominated the northern scene as the superior and most sophisticated weapon for hunting and perhaps warfare as well. As is so often the case with archaeology, we know not where it originally came from, or who first invented it, and we don’t know the reasons why it fell into disuse after approximately 5,000 years of a successful career. Fortunately though, we have a number of artefacts speaking to us of a time at the very dawn of archery history.